Most organizations treating government or enterprise procurement as a straightforward vendor-vetting exercise miss a critical requirement: demonstrating that their information systems have undergone formal security authorization. This oversight creates friction during contract negotiation—friction that becomes particularly costly when procurement cycles stall because you cannot produce evidence that a senior official has formally accepted the operational risk of your platform. For vendors serving federal agencies or heavily regulated enterprises, this authorization carries a specific designation: Authorization to Operate (ATO).

What is Authorization to Operate (ATO)?

Authorization to Operate represents an official management decision given by a senior Federal official to authorize operation of an information system and to explicitly accept the risk to agency operations based on the implementation of an agreed-upon set of security and privacy controls. While this definition originates from federal government practice, the underlying discipline applies broadly: an ATO is a formal declaration issued by a senior agency official that authorizes an information system to operate in a particular security environment for a certain period of time, based on the implementation and validation of its security controls and the assessment of residual risk.

The authorization rests on four critical components: a documented decision by senior leadership, explicit approval for system operation, formal acceptance of residual risk, and verified implementation of security and privacy controls. Both "Authorization to Operate" and "Authority to Operate" are used interchangeably in practice, though federal guidance standardizes on "authorization."

Scope and context

The ATO requirement emerged from the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA), which mandates that every information system operated by or on behalf of the U.S. federal government meet FISMA standards, including system authorization signed by an Authorizing Official. While rooted in public-sector risk management frameworks—particularly the NIST Risk Management Framework (RMF)—the discipline extends into enterprise procurement. Organizations selling software-as-a-service platforms, managed services, or infrastructure to large corporate clients in finance, healthcare, or defense increasingly encounter ATO-equivalent requirements during vendor assessments.

The ATO functions as system-level approval, distinct from individual security clearances. Where clearances authorize personnel to access classified information, ATOs authorize systems to process information at specified sensitivity levels within defined operational boundaries. This system approval encompasses both access authorization—defining who and what may interact with the system—and operational authorization, confirming the system meets baseline security posture requirements for production use.

Why ATO matters – the purpose

1) Risk management and acceptance

The ATO process acknowledges that no system is ever 100% secure—risk is always present and evolving. Authorization forces organizations to document residual risk after implementing baseline controls, then compels senior leadership to formally accept that risk or reject system operation. This explicit acceptance creates accountability: the Authorizing Official acknowledges potential impact to mission, reputation, assets, individuals, and partner organizations. For vendors, demonstrating that your own senior leadership has formally accepted operational risk signals maturity to enterprise clients evaluating your security posture.

2) System approval and access authorization

The ATO functions as a green light for production deployment. It confirms the system operates within a defined authorization boundary—specific infrastructure, data types, user populations, and interconnections—under documented controls and monitoring requirements. Enterprise clients increasingly require vendors to articulate their authorization boundaries and demonstrate that systems processing client data operate under formal approval. Without this approval, clients face uncertainty: Has anyone with authority evaluated whether this vendor's operational risk is acceptable?

3) Compliance certification and meeting cybersecurity standards

ATO processes select appropriate baseline security controls using NIST SP 800-53, covering access control, incident response, audit logging, and configuration management. For vendors serving regulated sectors, aligning internal processes to ATO requirements demonstrates conformance to recognized frameworks. Federal agencies expect alignment with NIST SP 800-53; financial services clients may require similar rigor under their third-party risk management programs; healthcare organizations expect controls protecting electronic protected health information (ePHI). Adopting ATO-equivalent processes provides a structured approach to meeting these varying regulatory compliance demands through a common control baseline.

4) Competitive advantage and client trust

Vendors that document formal authorization decisions—even internal ATOs for non-government contracts—differentiate themselves during procurement. Request for Proposal (RFP) responses strengthened by evidence of senior-level risk acceptance, documented control implementation, and continuous monitoring capabilities stand out. This becomes particularly valuable in supply-chain risk assessments, where clients evaluate not only your current security posture but also your governance maturity: Do you have processes ensuring ongoing authorization validity as your system evolves?

Real-world importance: preventing failures, protecting reputation and assets

Authorization processes protect against operational failures stemming from unmanaged risk. When vendors skip formal risk assessment and senior-level review, they operate systems that may appear secure superficially while harboring critical vulnerabilities or policy gaps. These gaps surface during incidents—at which point clients discover the vendor never formally evaluated whether their security controls matched their operational risk profile. ATO processes prevent this outcome by forcing systematic evaluation before production deployment. For enterprise sales contexts, clients increasingly demand evidence of authorization or equivalent risk assessment before onboarding vendor systems that will process sensitive data, integrate with corporate networks, or support critical business functions.

The ATO process: step-by-step for enterprise-vendor context

1) Preparatory phase: categorization and boundary setting

The ATO process begins with system categorization based on the sensitivity of information systems, following FIPS 199 guidelines that evaluate confidentiality, integrity, and availability. Organizations assess potential impact across these three dimensions—rating each as low, moderate, or high impact based on potential damage from compromise. Vendors must define system boundaries: which infrastructure, applications, data repositories, and third-party integrations fall within the authorization scope? This boundary definition determines which controls apply and identifies inherited controls—security capabilities provided by underlying infrastructure (such as cloud providers) that the vendor can leverage rather than implement independently.

2) Selection and implementation of controls

Select the security and privacy control baseline appropriate to your system's categorization. Moderate-impact systems typically require 300+ controls from NIST SP 800-53; high-impact systems demand additional controls and enhanced rigor. Document control implementation details: which policies govern the control, which technical measures enforce it, which personnel are responsible, and how the control operates in your specific architecture. This documentation becomes the System Security Plan (SSP)—the authoritative reference describing your security posture. For vendors, the SSP demonstrates to enterprise clients that you have systematically addressed security requirements rather than applying ad hoc measures.

3) Security assessment and authorization decision

Independent audit produces the Security Assessment Report (SAR), consolidating findings on vulnerabilities, weaknesses, and overall control effectiveness—a key component of the Authorization to Operate package demonstrating comprehensive and impartial review. Assessment activities include vulnerability scanning, penetration testing, configuration reviews, policy audits, and interviews validating that documented controls actually operate as described. Assessment findings feed into a Plan of Action and Milestones (POA&M) documenting residual weaknesses, remediation plans, and target completion dates. The Authorizing Official reviews the assessment package—SSP, SAR, POA&M, and risk assessment—then renders the authorization decision: grant full ATO, issue conditional authorization with restrictions, or deny authorization pending remediation.

4) Operation with continuous monitoring

ATO must be renewed every 3 years or after major changes to a system. Between authorizations, organizations maintain continuous monitoring programs: ongoing vulnerability scanning, log analysis, configuration compliance checking, and incident tracking. When assessment identifies new vulnerabilities or when the organization implements changes, security teams evaluate whether changes remain within the authorized boundary or trigger reauthorization requirements. This continuous monitoring provides ongoing assurance to both internal leadership and external clients that the system maintains its authorized security posture.

5) Renewal or update of authorization

A significant change to a system can require an update to its ATO—defined as a change likely to substantively affect the security or privacy posture of a system. Significant changes include upgraded hardware or applications, changes in collected information or handling procedures, modifications to system ports or services, new integrations, or expanded user populations. Organizations perform Security Impact Analysis (SIA) when changes occur, determining whether the change remains minor (requiring only documentation updates) or triggers reauthorization. Vendors serving long-term enterprise contracts should establish change management processes aligned with this discipline, notifying clients when significant changes occur and providing updated authorization documentation.

6) Mapping this process to enterprise vendor context

Vendors not serving federal agencies still benefit from adopting ATO-equivalent processes internally. Treat your service platform as the system requiring authorization. Perform risk assessment based on the sensitivity of client data you will process. Select control baselines from NIST SP 800-53, ISO 27001, or industry-specific frameworks. Document your implementation in an SSP or equivalent security documentation. Engage independent assessors to validate control effectiveness. Present the authorization package to your executive leadership—your CEO, CTO, or Board—and obtain formal risk acceptance documented in authorization correspondence or Board minutes. Provide this authorization evidence to enterprise clients during procurement, demonstrating that senior leadership has explicitly accepted operational risk and that your security posture has undergone independent verification.

Real-world applications and importance for companies selling to enterprise clients

Typical scenarios

Cloud service providers offering infrastructure, platform, or software services to government or regulated enterprises encounter direct ATO requirements. A SaaS vendor processing federal agency data must obtain FedRAMP authorization—a standardized ATO allowing reuse across agencies. Managed service providers operating security operations centers, IT infrastructure, or compliance programs for enterprise clients face contractual requirements for system approval and evidence of security assessment. Vendors included in enterprise procurement lists or approved vendor registries must demonstrate authorization status as a condition of eligibility.

Supply-chain, vendor management and network protection

Enterprise third-party risk management programs increasingly require vendors to demonstrate access authorization controls—who can access client data and under what conditions—alongside security assessment results and regulatory compliance status. Vendors with documented ATOs or equivalent authorization reduce procurement friction because they provide enterprise security teams with ready evidence addressing standard evaluation criteria. Supply-chain risk assessments evaluate not just current security posture but also governance processes ensuring ongoing security: How do you manage changes? How do you detect and respond to incidents? How do you ensure controls remain effective? ATO processes directly address these questions through continuous monitoring and reauthorization requirements.

Regulatory and compliance drivers

Financial services organizations operating under GLBA, PCI-DSS, or FFIEC examination requirements expect vendors to demonstrate cybersecurity standards conformance. Healthcare entities subject to HIPAA require business associates to implement administrative, physical, and technical safeguards—controls directly mappable to NIST SP 800-53 baselines used in ATO processes. Defense contractors and subcontractors must meet CMMC (Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification) requirements, which explicitly reference NIST frameworks underlying ATO. Having undergone ATO or equivalent authorization signals vendor readiness to meet these regulatory compliance drivers without requiring clients to build control validation programs from scratch.

Business benefit: faster contracting, reduced audit burden, improved trust

Vendors delivering authorization packages early in procurement cycles shorten time-to-contract. Rather than iterating through multiple rounds of security questionnaires while clients attempt to assess control implementation, vendors providing pre-authorized documentation answer client questions immediately. The authorization decision—documented evidence that senior leadership formally accepted risk—serves as a proof point for enterprise clients' internal auditors, external auditors, and regulators evaluating third-party risk management programs. Clients can document to their stakeholders: "We verified that vendor leadership explicitly accepted operational risk based on independent security assessment."

Challenges and common issues

Federal ATO processes consume substantial time and resources—12 to 18 months for cloud service provider FedRAMP authorizations, with comparable timelines for agency-specific ATOs. Documentation requirements are extensive: comprehensive SSPs, detailed control implementation statements, architectural diagrams, data flow documentation, interconnection agreements, incident response plans, contingency plans, and continuous monitoring strategies. For vendors unfamiliar with structured security assessment frameworks, mapping existing practices to NIST requirements presents challenges. Enterprise clients exhibit varying maturity: some demand federal-grade rigor; others accept lighter-weight vendor assessments. Vendors must adapt their authorization approach to client expectations while maintaining sufficient rigor to demonstrate genuine security rather than performative compliance.

Types of Authorization (and differences)

Different authorization types exist within federal contexts, providing vendors with vocabulary to navigate client requirements and position their security posture appropriately.

1) Full ATO (Authorization to Operate)

Traditional full authorization granted after comprehensive risk assessment, control implementation verification, independent security assessment, and formal acceptance by the Authorizing Official. This represents the standard authorization model: complete evaluation of a system within a defined boundary, documented in a full authorization package, valid for a specified period (typically three years) subject to continuous monitoring requirements.

2) Provisional ATO (P-ATO) and interim authorizations

FedRAMP issues Provisional ATOs for cloud service offerings, allowing federal agencies to grant their own ATOs (reusing the FedRAMP authorization) rather than conducting independent assessments. The P-ATO reduces duplication: a cloud provider obtains FedRAMP P-ATO once, then individual agencies issue ATOs recognizing the P-ATO rather than repeating the full assessment. Interim authorizations allow temporary operation based on preliminary assessment results, typically when organizations need limited production deployment while completing full authorization activities.

3) Authority to Use (ATU)

FedRAMP distinguishes between ATO and ATU: ATUs represent lighter-weight authorizations for shared systems, reusing existing ATOs rather than conducting separate full assessments. A cloud service offering requires at least one ATO on file with FedRAMP; additional agencies may then issue ATUs recognizing the existing authorization rather than duplicating assessment efforts. ATU provisions reduce administrative burden when multiple agencies consume the same authorized service under similar risk conditions.

4) Continuous Authorization (cATO) and ongoing authorization

Continuous Authorization to Operate represents the state achieved when organizations demonstrate sufficient maturity maintaining resilient cybersecurity posture that traditional periodic risk assessments and authorizations can transition to ongoing authorization models. Rather than three-year authorization cycles with point-in-time assessments, cATO emphasizes continuous assessment through automated monitoring, real-time risk evaluation, and dynamic authorization decisions. Organizations operating under cATO maintain authorization through demonstrated security maturity, automated compliance validation, and continuous control effectiveness monitoring rather than periodic manual review cycles.

Why does this matter for vendors?

Understanding authorization types allows vendors to position their security posture appropriately during client conversations. When enterprise clients request "ATO-equivalent documentation," clarify whether they expect full authorization packages, continuous monitoring evidence, or lighter-weight authorization memos recognizing inherited controls. For vendors serving multiple enterprise clients with similar requirements, consider whether you can establish one comprehensive authorization that subsequent clients recognize—analogous to FedRAMP's P-ATO model—rather than repeating full assessment for each client. Global vendors may adopt hybrid approaches: internal ATO-style authorization processes producing documentation adaptable to varying client requirements across industries and geographies.

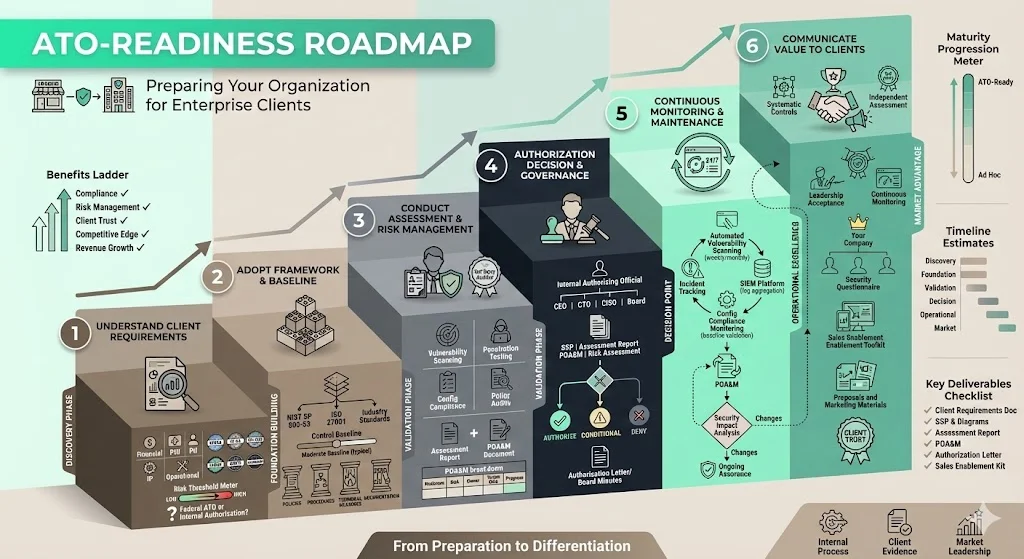

How to prepare your organization (vendor) to support enterprise clients with ATO-readiness

1) Understand the client's risk and compliance requirements

Begin by identifying what data you will process and at what sensitivity level. Financial account data, protected health information, personally identifiable information, intellectual property, and operational data carry different regulatory implications and risk thresholds. Determine which regulatory frameworks apply to your client: HIPAA for healthcare, GLBA or PCI-DSS for financial services, CMMC for defense contractors, GDPR for European data, FedRAMP or agency-specific requirements for federal systems. Map these requirements to cybersecurity standards and determine the expected system approval threshold: Does your client require full federal-grade ATO, or will internal authorization with independent assessment suffice?

2) Adopt a framework and controls baseline

Align with NIST SP 800-53 if serving government or defense clients; adopt ISO 27001 for international enterprise clients; reference industry-specific standards such as PCI-DSS for payment processing or HITRUST for healthcare. Select the control baseline matching your system categorization—typically NIST SP 800-53 moderate baseline for enterprise services processing sensitive but unclassified data. Document policies governing each control requirement. Develop procedures implementing those policies. Deploy technical measures enforcing controls. Create system diagrams, network architecture documentation, and data flow diagrams supporting your SSP. This documentation demonstrates systematic control implementation rather than ad hoc security measures.

3) Conduct internal security assessment and risk management

Engage independent assessors—third-party auditors with no operational responsibility for your system—to evaluate control effectiveness. Assessment should include vulnerability scanning across all system components, penetration testing simulating attacker techniques, configuration compliance validation against established baselines, and policy audits confirming documented procedures match operational reality. Document findings in assessment reports. Establish a Plan of Action and Milestones (POA&M) for identified weaknesses: describe each weakness, assess its risk severity, assign remediation ownership, define target completion dates, and track progress. The POA&M demonstrates to enterprise clients that you systematically manage residual risk rather than ignoring assessment findings.

4) Define the authorization decision and governance

Identify the internal senior official with authority to accept operational risk on behalf of your organization—typically your CEO, CTO, CISO, or Board of Directors depending on organizational governance structure. This individual functions as your internal Authorizing Official. Present the authorization package: SSP describing your controls, assessment report documenting independent evaluation, POA&M addressing residual weaknesses, and risk assessment summarizing overall system risk posture. The Authorizing Official reviews the package and renders a formal decision: authorize operation, authorize with conditions, or deny authorization pending remediation. Document this decision in authorization correspondence, Board minutes, or formal authorization memos. This documented decision provides evidence to enterprise clients that senior leadership explicitly accepted your system's operational risk.

5) Monitor continuously and maintain posture

Establish continuous monitoring programs operating after authorization. Deploy automated vulnerability scanning on weekly or monthly cycles. Configure security information and event management (SIEM) platforms aggregating logs and detecting anomalies. Implement configuration compliance monitoring validating systems remain within authorized configuration baselines. Track incidents and analyze root causes. Maintain the POA&M as a living document, updating remediation status and adding newly identified weaknesses. When implementing system changes, perform Security Impact Analysis determining whether changes remain within authorized boundaries or require reauthorization. This continuous monitoring provides ongoing assurance—to your leadership and your clients—that you maintain authorized security posture rather than allowing security to degrade between authorization cycles.

6) Communicate value to enterprise clients

Incorporate authorization language into marketing materials, proposals, and RFP responses. Articulate that your organization has adopted ATO-equivalent authorization processes: systematic control implementation based on recognized frameworks, independent security assessment validating control effectiveness, senior leadership risk acceptance documented in formal authorization decisions, and continuous monitoring maintaining authorized posture. Position this as differentiation: while competitors provide generic security questionnaire responses, you provide evidence of formal authorization undergone by your own organization. Use authorization documentation as sales enablement—providing security teams with substantive evidence addressing their evaluation criteria and accelerating their vendor approval processes.

Common myths and clarifications

Organizations new to authorization processes often hold misconceptions that create risk or lead to inadequate implementation.

Myth #1: "Once you have an ATO you're done forever." Authorization is never permanent. Without an active ATO, systems cannot stay live; if ATO expires or isn't renewed, everything must be taken down until compliance is reestablished. Continuous monitoring, ongoing risk assessment, and periodic reauthorization—typically every three years or when significant changes occur—are inherent requirements. Organizations must resource authorization maintenance, not treat it as a one-time project.

Myth #2: "ATO is only for the federal government." While ATO originated in federal FISMA requirements, enterprise clients increasingly expect equivalent rigor. Regulated industries, security-conscious enterprises, and organizations managing third-party risk demand evidence that vendors have undergone formal authorization processes. Many suppliers pursuing commercial enterprise contracts discover that demonstrating ATO-equivalent processes accelerates procurement even when clients don't explicitly require federal authorization.

Myth #3: "ATO means zero risk." No system is ever 100% secure—risk is always present and evolving. Authorization signifies accepted residual risk and documented controls, not risk elimination. The Authorizing Official explicitly accepts that residual risk exists after implementing baseline controls. Organizations must communicate this to stakeholders: authorization means we understand our risk, have implemented appropriate controls, and accept remaining risk—not that risk is absent.

Myth #4: "We just need a certificate and that's enough." Authorization is not certification. Certifications such as ISO 27001 or SOC 2 demonstrate control implementation and independent audit; authorization represents a formal management decision accepting operational risk. The distinction matters: certification shows you implemented controls, authorization shows leadership formally accepted responsibility for operating under residual risk. Both are valuable; neither replaces the other.

Organizations must also understand distinctions between authorization types: full ATO requires comprehensive assessment; ATU reuses existing authorizations for shared systems; cATO represents maturity-based ongoing authorization rather than periodic review cycles. Clarifying which authorization type applies to your context prevents misalignment between vendor capabilities and client expectations.

Conclusion

For organizations selling to enterprise clients (especially government, regulated industries, or security-mature corporations), Authorization to Operate (ATO) is critical. It systematically demonstrates your system meets rigorous security standards, risks have been assessed and formally accepted by senior leadership, and continuous monitoring is in place for trusted operations. Adopting ATO practices accelerates procurement, strengthens vendor evaluation, builds trust, and disciplines risk management using recognized frameworks.

Authorization processes shorten procurement cycles, reduce audit burdens (as clients leverage existing assessments), improve security through systematic control and continuous monitoring, and provide competitive differentiation.

Start ATO efforts early. Structure processes around recognized frameworks (NIST RMF, ISO 27001). Build comprehensive documentation proving controls are implemented, assessed, and monitored. Engage stakeholders: assessors, senior leadership (for risk acceptance), and client security teams. Continuously monitor control effectiveness, remediate weaknesses (via POA&Ms), and reassess after significant changes.

Integrate ATO into sales and service assurance. Train sales teams on its value, provide supporting documentation, and position it as evidence of operational maturity, not just compliance. This transforms ATO from a bureaucratic requirement into a competitive advantage, demonstrating security as an operational discipline backed by accountability, validation, and continuous improvement.

FAQs

1) What is the purpose of ATO?

Authorization to Operate provides a formal, senior-level decision approving a system's operation under explicitly accepted risk. It ensures security and privacy controls are implemented, that independent assessment has validated control effectiveness, and that an Authorizing Official accepts residual risk of operations including potential impact to mission, reputation, assets, individuals, and partner organizations.

2) What is the difference between ATO and ATU?

An ATO (Authorization to Operate) represents full authorization of a system following comprehensive security assessment, control implementation verification, and formal risk acceptance. An ATU (Authority to Use) is a lighter-weight authorization reusing an existing ATO rather than conducting full independent assessment—commonly used when multiple agencies consume the same cloud service that already holds a FedRAMP ATO, allowing agencies to issue ATUs recognizing the existing authorization.

3) Who provides the authorization to operate?

A senior organizational or agency official—commonly designated the Authorizing Official (AO)—grants the ATO by formally accepting residual risk of operating the information system. In federal contexts this is typically a Senior Agency Official or equivalent; in enterprise vendor contexts this may be the CEO, CTO, CISO, or Board of Directors depending on organizational governance structure and risk tolerance thresholds.

4) What are the three types of authorization?

While frameworks label authorization types differently, typical distinctions include: (1) Full ATO—comprehensive authorization following complete assessment of a system within defined boundaries, valid for a specified period subject to continuous monitoring; (2) ATU (Authority to Use) or similar reuse authorization for shared systems, providing lighter-weight authorization recognizing existing ATOs rather than duplicating assessment; (3) Continuous Authorization (cATO)—ongoing authorization based on demonstrated security maturity, automated monitoring, and continuous assessment rather than periodic point-in-time reviews requiring reauthorization every three years.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)