Most organizations treating CUI as an afterthought to traditional information security programs misunderstand the regulatory landscape. CUI formally acknowledged that certain types of unclassified information are extremely sensitive, valuable to the United States, sought after by strategic competitors and adversaries, and often have legal safeguarding requirements. This isn't aspirational guidance—it's a binding operational standard enforced through federal contracts, with failure to comply resulting in contract challenges, loss of awards, future ineligibility for government contracts, and potential fraud charges with criminal penalties.

This glossary term provides operational teams and technical leaders with a comprehensive understanding of CUI requirements: what qualifies as CUI, why the program exists, where compliance obligations originate, and how organizations handling federal information must implement specific safeguarding and dissemination controls.

What is Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI)?

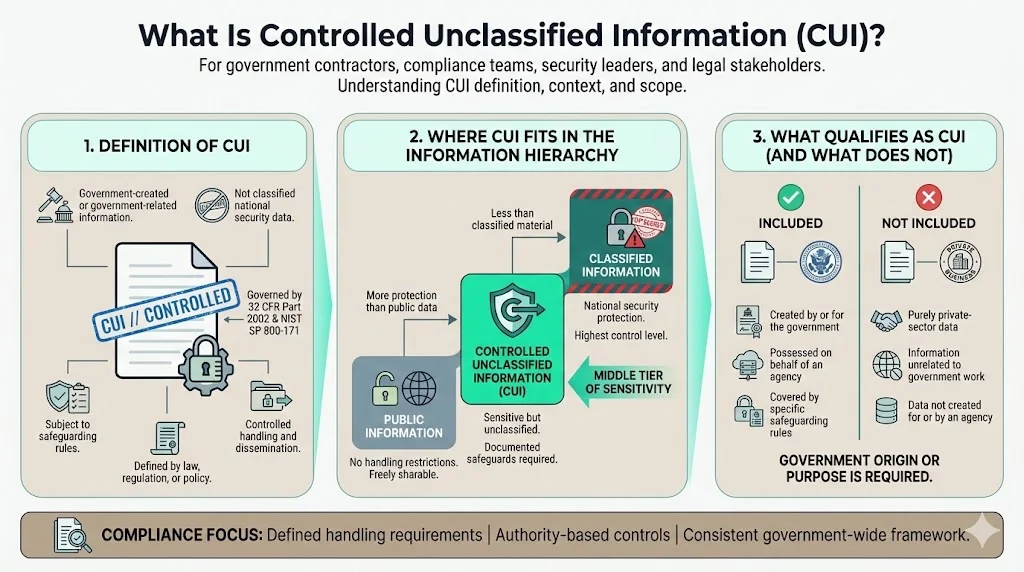

CUI is information the Government creates or possesses, or that an entity creates or possesses for or on behalf of the Government, that a law, regulation, or Government-wide policy requires or permits an agency to handle using safeguarding or dissemination controls. The critical distinction: CUI isn't classified national security information governed by Executive Order 13526 or the Atomic Energy Act, yet it demands specific protective measures beyond standard unclassified data handling.

CUI exists in a distinct tier of the information classification hierarchy. Where public information requires no controls and classified information demands stringent national security protections, CUI occupies the middle ground—unclassified but sensitive, requiring documented safeguards based on specific legal or regulatory authorities. CUI does not include information a non-executive branch entity possesses and maintains in its own systems that did not come from, or was not created or possessed by or for, an executive branch agency—the government origin or purpose is definitional.

Why CUI Exists

Executive Order 13556 establishes a program for managing CUI across the Executive branch and designates the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) as the Executive Agent to implement the Order and oversee agency actions to ensure compliance. Issued in November 2010, the Order responded to systemic deficiencies in how federal agencies and their partners protected sensitive unclassified information.

Before CUI standardization, agencies applied inconsistent markings—For Official Use Only (FOUO), Sensitive But Unclassified (SBU), Law Enforcement Sensitive (LES)—creating confusion about handling requirements and inadequate protection for legitimately sensitive data. The CUI Program is designed to address several deficiencies in managing and protecting unclassified information, including inconsistent markings, inadequate safeguarding, and needless restrictions, by standardizing procedures and providing common definitions through a CUI Registry.

CUI marking replaces legacy markings such as For Official Use Only (FOUO) or Sensitive But Unclassified (SBU). This unification matters operationally: contractors working across multiple agencies now follow consistent safeguarding protocols rather than navigating agency-specific requirements that previously created compliance gaps and interoperability failures.

Common Examples of CUI

The CUI Registry—maintained by NARA at archives.gov/cui—serves as the authoritative reference for all approved CUI categories. All unclassified information that qualifies as CUI must be handled within the parameters of the CUI Program and marked appropriately per the CUI Registry. Only information types explicitly listed in the Registry with corresponding legal or regulatory authority qualify as CUI.

Common CUI categories encountered in federal contracting include:

- Privacy Information: Personally Identifiable Information (PII) requiring protection under the Privacy Act of 1974, health information subject to HIPAA, or financial records governed by specific statutes. These data types become CUI when created or possessed on behalf of the federal government.

- Proprietary Business Information: Trade secrets, commercial or financial information obtained from entities under promises of confidentiality, procurement-sensitive data, or source selection information protected under federal acquisition regulations.

- Export Controlled Information: Technical data subject to International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) or Export Administration Regulations (EAR) when possessed or created for government purposes. Defense contractors frequently handle technical drawings, specifications, and design documentation that qualify as both CUI and export-controlled.

- Legal Information: Law enforcement investigative information, attorney work product, attorney-client privileged communications, or litigation materials held by federal agencies or entities acting on their behalf.

- Critical Infrastructure Information: Operational or technical data about systems and assets whose incapacity would have debilitating effects on security, economic security, public health, or safety.

Each category in the CUI Registry cites the specific law, regulation, or government-wide policy creating the protection requirement—providing the legal foundation for handling controls and penalties for unauthorized disclosure.

How CUI Fits into Information Security and Data Protection

Data Classification and Governance

CUI occupies a specific position within enterprise data classification schemes. Organizations handling federal information typically implement four-tier classification frameworks:

Public: Information intended for unrestricted public access with no confidentiality requirements.

Internal Use: Proprietary business information requiring basic access controls but not subject to specific regulatory safeguarding mandates.

Controlled Unclassified Information: Government-origin or government-purpose information requiring specific safeguarding and dissemination controls per 32 CFR Part 2002 and the CUI Registry.

Classified: National security information requiring protection at Confidential, Secret, or Top Secret levels under Executive Order 13526.

This classification architecture ensures CUI receives protections commensurate with its legal requirements—more stringent than routine business data but distinct from classified national security information requiring security clearances and specialized facilities.

CUI and Sensitive Data Management

32 CFR Part 2002 establishes policy for agencies on designating, safeguarding, disseminating, marking, decontrolling, and disposing of CUI, self-inspection and oversight requirements, and other facets of the Program. These regulations create binding operational requirements for how organizations identify, label, protect, share, and ultimately decontrol or destroy CUI throughout its lifecycle.

Safeguarding requirements vary by CUI category. CUI Basic requires agencies to control or protect the information but provides no specific controls, while CUI Specified requires agencies to control or protect the information and provides specific controls for doing so. Organizations must consult the CUI Registry to determine whether each category demands basic or specified controls—a distinction that directly impacts implementation complexity and cost.

Marking serves as the primary mechanism for conveying CUI status and handling requirements. The standard CUI marking is the acronym CUI, appearing centered across the top of every page of any document with sensitive information in bold font, large enough to be readily visible. Additional category markings and dissemination controls may accompany the base CUI marking when specified controls apply.

Ties to Cybersecurity Standards

CUI requirements intersect directly with NIST cybersecurity frameworks that define technical and administrative controls for federal information systems. Systems that include CUI must incorporate the requirement to safeguard CUI at the moderate confidentiality impact value into their design and management actions. This maps to FIPS 199 impact categorization and drives control selection from NIST Special Publication 800-53.

For federal contractors—particularly defense contractors—NIST SP 800-171 provides the primary security control baseline. This publication specifies 110 security requirements derived from FIPS 200 and NIST SP 800-53 specifically tailored for protecting CUI in nonfederal systems and organizations. Contractors must implement these controls in any system where CUI resides, transits, or is processed—creating substantial infrastructure and operational requirements.

The controls span 14 families: access control, awareness and training, audit and accountability, configuration management, identification and authentication, incident response, maintenance, media protection, personnel security, physical protection, risk assessment, security assessment, system and communications protection, and system and information integrity. Each requirement includes specific implementation guidance and assessment procedures auditors use to verify compliance.

Regulatory Compliance and Risk Management

Legal and Policy Drivers

CUI obligations originate from multiple legal and policy sources that collectively create a comprehensive regulatory framework:

Executive Order 13556: The foundational authority establishing the CUI Program, designating NARA as Executive Agent, and directing uniform implementation across executive branch agencies.

32 CFR Part 2002: The implementing regulation codifying CUI requirements, including designation criteria, marking standards, safeguarding controls, dissemination limitations, decontrol procedures, and oversight mechanisms. This regulation carries the force of federal law.

Agency-Specific Implementation: Individual agencies like the Department of Defense, Department of Energy, Environmental Protection Agency, and Department of the Interior have issued supplementary policies adapting CUI requirements to mission-specific contexts while maintaining consistency with the government-wide program.

Contractual Flow-Down: Federal contracts incorporate CUI requirements through specific clauses that obligate contractors and subcontractors to implement prescribed controls. For DoD contracts, DFARS clause 252.204-7012 mandates NIST SP 800-171 compliance as a contractual requirement.

The regulatory architecture creates direct liability chains: agencies must protect CUI in their systems; contractors must protect CUI in their systems; violations can trigger contract termination, suspension or debarment from federal contracting, civil penalties, and in cases of willful or negligent disclosure, criminal prosecution under underlying statutes.

Who Must Comply with CUI Requirements

The rule affects Federal executive branch agencies that handle CUI and all organizations that handle, possess, use, share, or receive CUI—or which operate, use, or have access to Federal information and information systems on behalf of an agency. This reaches beyond direct contractors to subcontractors, research institutions, universities, state and local governments, and any entity that creates, receives, or processes information on behalf of a federal agency.

Compliance obligations activate when contracts or agreements specify CUI protection requirements. Defense contractors receiving technical data packages, research institutions conducting federally funded studies involving human subjects data, IT service providers hosting federal systems, and professional services firms handling procurement-sensitive information all fall within CUI scope when their work involves government-origin or government-purpose information.

The compliance burden extends throughout the supply chain. Prime contractors bear responsibility for ensuring subcontractors implement adequate controls—creating vendor management and third-party risk assessment obligations that cascade through multiple organizational tiers.

CUI and Federal Contracts

Federal acquisition regulations and agency-specific supplements incorporate CUI requirements directly into contract terms and conditions. For Department of Defense contracts, Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS) clause 252.204-7012 requires contractors to implement NIST SP 800-171 controls, report cybersecurity incidents involving CUI within 72 hours, and submit attestations or certifications of compliance.

The DFARS clause creates assessment requirements: contractors must conduct self-assessments, potentially undergo medium or high assessments conducted by third-party assessment organizations, and maintain documentation demonstrating control implementation and effectiveness. The Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA) and Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency (DCSA) conduct compliance verification through contract audits.

Non-compliance carries tangible consequences. Contracting officers can withhold payments, terminate contracts for default, or initiate suspension and debarment proceedings. Beyond immediate contract impacts, poor compliance records damage an organization's past performance ratings—directly affecting competitiveness for future awards. In a procurement environment where past performance often weighs as heavily as technical capability and price, CUI compliance failures create lasting business damage.

Other agencies increasingly adopt similar contractual mechanisms. NASA, the Department of Energy, and civilian agencies incorporate CUI protection clauses into their contracts, often referencing NIST SP 800-171 or agency-specific control baselines. The trend is clear: CUI compliance transitions from recommended practice to contractual mandate across the federal procurement landscape.

Privacy Safeguards and Information Governance

CUI protection intersects with broader privacy and information governance frameworks. When CUI includes PII—which it frequently does—organizations must satisfy both CUI safeguarding requirements and privacy protection obligations under the Privacy Act, HIPAA, or other applicable statutes. These requirements aren't duplicative; they're complementary, with CUI providing the handling framework and privacy laws specifying use limitations and individual rights.

Organizations building effective CUI programs integrate these obligations into comprehensive information governance frameworks. This includes data inventories identifying what CUI the organization possesses, data flow mapping showing how CUI moves through systems and processes, retention schedules determining how long CUI must be maintained, and disposition procedures ensuring secure destruction when no longer needed.

Framework integration is essential. Organizations already implementing ISO/IEC 27001 Information Security Management Systems can map CUI controls to existing practices, identifying gaps requiring remediation. Similarly, organizations with mature NIST Cybersecurity Framework implementations can incorporate CUI-specific requirements into their existing risk management processes rather than building parallel compliance programs.

Practical Data Handling Procedures

1) Identification and Marking

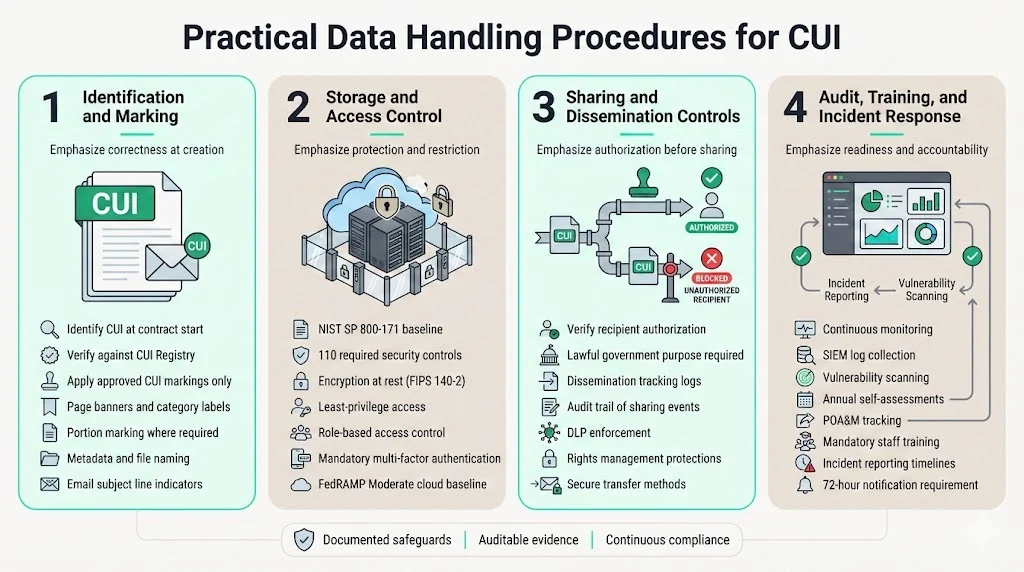

Organizations must establish systematic procedures for identifying information that qualifies as CUI. This begins at contract inception: acquisition documents, statements of work, and data requirements specifications should explicitly identify what information the government considers CUI. Contracting officers and program managers bear responsibility for providing this guidance, but contractors must independently evaluate whether information they create or derive during contract performance meets CUI criteria.

Only items that fall under the purview of the CUI Registry may be marked as CUI, and items can only be marked according to CUI Markings identified in the CUI Registry. This requires personnel to consult the Registry, understand category definitions, and apply appropriate markings. Training programs must ensure employees can reliably distinguish CUI from uncontrolled unclassified information—a skill requiring familiarity with legal and regulatory authorities underlying each category.

Marking requirements apply to physical and electronic formats. Documents require CUI banners at the top and bottom of each page, along with category-specific markings when applicable. Portion marking—applying CUI indicators to individual paragraphs or sections—is required in some contexts but optional in others. Electronic files require embedded metadata or file naming conventions that preserve CUI markings when information is extracted, copied, or transmitted. Email subject lines must include CUI indicators when messages contain or attach controlled information.

2) Storage and Access Control

CUI must reside in systems meeting prescribed security control baselines. For contractors subject to NIST SP 800-171, this means implementing 110 security requirements addressing system hardening, encryption, access control, monitoring, and incident response. Systems storing CUI require encryption at rest using FIPS 140-2 validated cryptographic modules—commercial off-the-shelf solutions must carry appropriate certifications.

Access control follows the principle of least privilege: individuals receive access only to the specific CUI necessary for their assigned duties. Role-based access control (RBAC) models work well for CUI environments, with roles defined by job function and CUI access granted based on demonstrated need-to-know. Multi-factor authentication is mandatory for CUI system access under NIST SP 800-171, adding device-based or biometric verification to traditional passwords.

Physical security matters even in cloud-centric environments. Data centers hosting CUI systems—whether contractor-operated or cloud service provider facilities—must implement physical access controls, environmental protections, and monitoring systems. FedRAMP Moderate authorization serves as the baseline for cloud service providers handling CUI, providing independent verification that infrastructure controls meet federal requirements.

3) Sharing and Dissemination Controls

CUI dissemination—the act of sharing controlled information—requires verifying recipient authorization before release. Recipients may include State, Local, Tribal and Territorial Governments, appropriate industrial partners, other Federal Agencies, Allies and Partner nations, and members of academia—but only when they have a lawful government purpose for accessing the information.

Organizations must implement dissemination tracking mechanisms documenting who received what CUI, when it was shared, and under what authority. This creates an audit trail supporting incident investigation if unauthorized disclosure occurs and demonstrating compliance during contract audits.

Technical controls support dissemination restrictions. Data Loss Prevention (DLP) solutions can identify CUI markings and enforce transmission policies—blocking or flagging emails to unauthorized domains, preventing uploads to non-approved cloud storage, or requiring additional approval workflows before external sharing. Rights management technologies can embed persistent protection in CUI documents, preventing copying, printing, or forwarding even after initial dissemination.

Controlled formats become important for CUI sharing. PDFs with embedded security settings, secure file transfer protocols, and dedicated collaboration portals provide more control than unrestricted file formats. The Department of Defense SAFE (Secure Access File Exchange) service exemplifies purpose-built solutions for CUI dissemination, providing encrypted transit and storage with access controls and audit logging.

4) Audit, Training, and Incident Response

CUI protection requires continuous monitoring and periodic assessment. Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) systems should collect logs from CUI systems, analyzing access patterns, configuration changes, and potential security events. Regular vulnerability scanning identifies technical weaknesses requiring remediation before exploitation.

Compliance audits verify control implementation and effectiveness. Organizations should conduct self-assessments at least annually, documenting control implementation, identifying deficiencies, and developing Plans of Action and Milestones (POA&Ms) for remediation. Third-party assessments provide independent verification increasingly required by federal contracts.

Training requirements extend to all personnel with CUI access. Staff shall be responsible for properly protecting, marking and otherwise handling CUI in accordance with all applicable policies, procedures, and guidance. Training must occur before granting CUI access, with annual refresher training reinforcing requirements. Training content should address identification, marking, safeguarding, dissemination, and incident reporting specific to the CUI categories the organization handles.

Incident response procedures must address CUI-specific scenarios. Any suspected or confirmed unauthorized disclosure triggers mandatory reporting to the contracting officer within timeframes specified by contract—often 72 hours. The incident response must include containment measures, damage assessment, notification to affected parties when PII is involved, and corrective actions preventing recurrence. For DoD contractors, the Department requires reporting through the DoD Cyber Crime Center (DC3) system with detailed information about what CUI was affected, how the breach occurred, and what remediation was implemented.

Common CUI Handling Mistakes

Organizations new to CUI protection consistently repeat predictable errors that create compliance gaps and operational risk:

1) Over-designation or Under-designation: Marking routine unclassified information as CUI creates unnecessary protection burden and operational friction. Conversely, failing to recognize CUI results in inadequate protection and regulatory violations. Both errors stem from insufficient training on CUI Registry categories and underlying legal authorities. The solution requires systematic classification reviews at document creation, with clear escalation paths for uncertain situations.

2) Inadequate Access Controls: Implementing perimeter security while allowing unrestricted internal access violates least-privilege principles. CUI systems require role-based access control with documented need-to-know justifications. Many organizations fail to regularly review access permissions, allowing privilege creep where individuals retain CUI access long after job responsibilities change. Quarterly access reviews should be mandatory for any system storing CUI.

3) Misunderstanding Dissemination Boundaries: Organizations sometimes assume CUI can be shared freely within their company or with business partners. CUI dissemination restrictions persist regardless of organizational boundaries—subcontractors require explicit authorization to receive CUI, and sharing for purposes beyond the contract scope violates dissemination controls. Employees need training on verifying recipient authorization before any CUI disclosure.

4) Segregating CUI from Cybersecurity Programs: Treating CUI compliance as a standalone initiative separate from enterprise cybersecurity creates redundant processes and control gaps. CUI requirements should integrate into existing security operations—vulnerability management, patch management, configuration management, incident response—with CUI-specific requirements augmenting rather than replacing existing practices. Security operations centers should incorporate CUI handling into their standard operating procedures rather than maintaining separate workflows.

5) Insufficient Subcontractor Management: Prime contractors remain liable for subcontractor CUI protection failures. Contracts must flow down CUI requirements with sufficient specificity, due diligence must verify subcontractor capability before CUI disclosure, and ongoing oversight must confirm sustained compliance. Many organizations conduct thorough initial assessments but fail to monitor subcontractor compliance throughout contract performance.

CUI and Enterprise Client Expectations

Enterprise clients—particularly those in aerospace, defense, professional services, and technology sectors serving government markets—increasingly demand CUI compliance from their vendors and partners. This expectation extends beyond direct government contractors to the broader ecosystem of service providers, software vendors, and infrastructure suppliers.

The rationale is straightforward: enterprise clients face contractual obligations and reputational risk when their vendors mishandle CUI. A cloud service provider's inadequate controls, a professional services firm's poor data handling, or a software vendor's insecure development practices can trigger client compliance failures, incident reporting obligations, and contract performance issues. Enterprises therefore extend CUI requirements through vendor agreements, security questionnaires, and periodic assessments.

Demonstrating mature CUI capabilities creates competitive differentiation. Vendors with established NIST SP 800-171 implementations, documented CUI handling procedures, and clean assessment records offer lower risk and faster procurement cycles. Enterprises can flow down CUI to these vendors with confidence, avoiding the delays and oversight burden associated with remediating vendor deficiencies.

This market dynamic increasingly separates vendors into two categories: those capable of handling CUI who can pursue government-facing contracts, and those without CUI capabilities relegated to commercial-only opportunities. For companies pursuing growth in government or aerospace sectors, CUI compliance has become table stakes rather than optional enhancement.

Conclusion

Controlled Unclassified Information represents a fundamental shift in how the federal government and its contractors protect sensitive unclassified data. What began as Executive Order 13556's response to inconsistent information safeguarding has evolved into a comprehensive regulatory framework with contractual enforcement mechanisms, technical control requirements, and direct consequences for non-compliance.

Organizations handling federal information—whether through direct contracts, subcontracts, research grants, or service agreements—must build proactive CUI programs that identify controlled information, implement prescribed safeguards, enforce dissemination controls, and maintain audit readiness. This requires investment in technical controls meeting NIST standards, development of policies and procedures addressing the complete CUI lifecycle, training for personnel throughout the organization, and integration with broader cybersecurity and information governance frameworks.

The compliance burden is substantial but unavoidable. Federal agencies increasingly enforce CUI requirements through contract audits, incident investigations, and performance evaluations. Contractors unable to demonstrate adequate CUI protection face contract termination, debarment from future opportunities, and reputational damage that extends beyond government markets into commercial sectors where clients demand proven information security capabilities.

Organizations that treat CUI compliance as an operational discipline rather than a documentation exercise—implementing genuine security controls that protect information while satisfying auditors—position themselves for sustained success in government contracting and adjacent markets where CUI capabilities create competitive advantage.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1) What is Controlled Unclassified Information?

Controlled Unclassified Information is information that requires safeguarding or dissemination controls pursuant to and consistent with applicable law, regulations, and government-wide policies but is not classified. It encompasses sensitive government-origin or government-purpose data requiring specific protection measures beyond routine unclassified information handling.

2) Who must comply with CUI requirements?

Federal executive branch agencies and all organizations that handle, possess, use, share, or receive CUI comply with CUI requirements. This includes federal contractors and subcontractors, research institutions conducting federally funded work, state and local governments performing federal functions, and any entity operating systems or handling information on behalf of federal agencies. Compliance obligations activate when contracts or agreements specify CUI protection requirements.

3) How is CUI different from classified data?

CUI is unclassified information not covered by Executive Order 13526 governing national security classified information or the Atomic Energy Act covering restricted data and formerly restricted data. CUI doesn't require security clearances or classified information systems. However, CUI demands specific safeguarding and dissemination controls based on laws, regulations, or government-wide policies authorizing protection for particular information categories. The sensitivity stems from statutory or regulatory requirements rather than national security classification decisions.

4) What are common CUI handling mistakes?

Organizations frequently fail to correctly identify what information qualifies as CUI, resulting in over-designation that burdens operations or under-designation that creates compliance violations. Inadequate access controls that allow unrestricted internal access while implementing only perimeter security violate least-privilege requirements. Misunderstanding dissemination boundaries leads to unauthorized sharing with subcontractors, partners, or for purposes beyond contract scope. Treating CUI as a standalone compliance program rather than integrating requirements into enterprise cybersecurity creates redundant processes and control gaps.

5) How does CUI connect to federal contracts?

Federal contracts incorporate CUI requirements through specific clauses obligating contractors to implement prescribed controls. DFARS clause 252.204-7012 mandates NIST SP 800-171 implementation for DoD contracts, requires cybersecurity incident reporting within 72 hours, and creates assessment obligations including self-assessments and potential third-party audits. Other agencies use similar contractual mechanisms. Non-compliance can trigger payment withholding, contract termination, suspension or debarment proceedings, and damage to past performance ratings affecting future competitiveness. CUI compliance has transitioned from recommended practice to binding contractual requirements with direct consequences for failure.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)