Most vendors underestimate how deeply federal security requirements influence enterprise procurement—even when they're not directly contracting with government agencies. FISMA regulations establish the baseline security posture expected across federal information systems, and those expectations cascade through supply chains, enterprise security questionnaires, and vendor risk assessments. Companies pursuing contracts with large enterprises, particularly those in healthcare, finance, or defense-adjacent sectors, routinely encounter FISMA-derived security requirements embedded in RFPs and security reviews.

This creates a practical challenge: organizations must understand FISMA's scope and technical requirements even when they're not formally subject to the law. The security controls, risk management disciplines, and continuous monitoring practices mandated by FISMA have become de facto standards for vendors serving regulated buyers. This definition explains what FISMA regulations require, who must comply, how the framework operates, and why FISMA readiness accelerates enterprise sales cycles for vendors operating in security-conscious markets.

What Are FISMA Regulations?

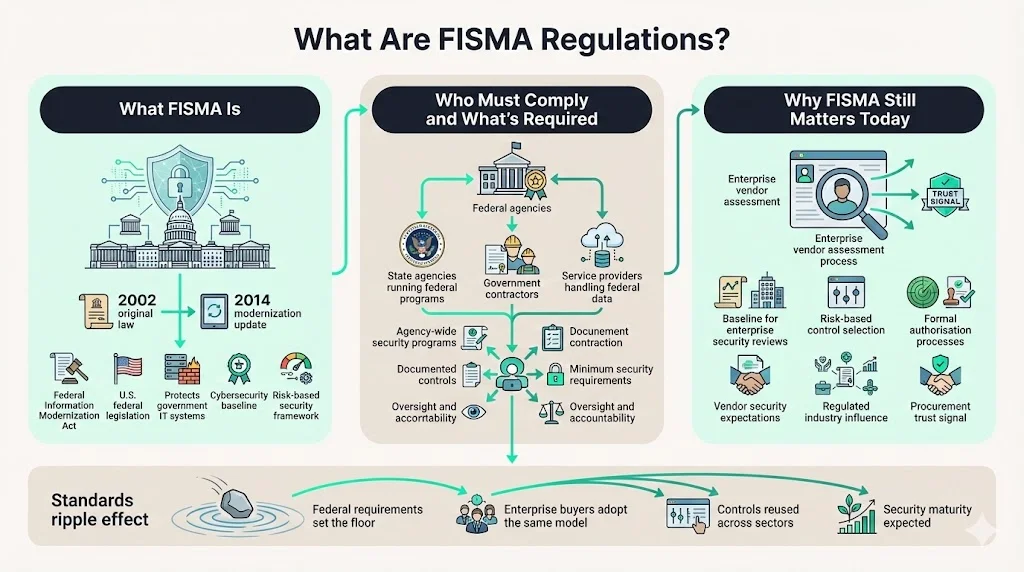

The Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA) is United States legislation that defines a framework of guidelines and security standards to protect government information technology operations from cyberthreats. The original FISMA was the Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002, in the E-Government Act of 2002. The law was amended by the Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014, passed in response to increasing cyber attacks on the federal government.

FISMA requires federal agencies to establish comprehensive information security programs and develop, document, and implement agency-wide information security programs. The law establishes minimum security requirements for federal information systems and assigns oversight responsibilities to ensure consistent implementation across government operations. While initially focused on federal agencies, FISMA's scope widened to apply to state agencies that administer federal programs as well as private businesses and service providers that hold a contract with the U.S. government.

FISMA remains relevant because its security requirements have become the baseline against which enterprise buyers evaluate vendor security posture. Organizations selling into heavily regulated industries encounter FISMA-derived security controls in vendor risk assessments, even when the ultimate customer is not a federal agency. The security disciplines FISMA mandates—risk-based control selection, continuous monitoring, formal authorization processes—are now standard expectations in enterprise procurement.

Who Enforces and Oversees FISMA

FISMA 2014 codifies the Department of Homeland Security's role in administering the implementation of information security policies for federal Executive Branch civilian agencies, overseeing agencies' compliance with those policies, and assisting OMB in developing those policies. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), operating under DHS, provides technical assistance, deploys technologies to federal systems, and administers operational security requirements.

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is the agency responsible for final oversight of the FISMA compliance efforts of each agency. OMB and DHS collaborate with interagency partners to develop the Chief Information Officer FISMA metrics, and with IG partners to develop the IG FISMA metrics. FISMA requires agencies to report the status of their information security programs to OMB and requires Inspectors General to conduct annual independent assessments of those programs.

For vendors and service providers, enforcement operates indirectly through contractual obligations and procurement requirements. Federal agencies assess contractor security programs as part of acquisition processes, and FISMA compliance gaps in vendor systems can disqualify organizations from contract consideration or trigger remediation requirements. Enterprise buyers mimicking federal procurement practices apply similar scrutiny, effectively extending FISMA's influence beyond direct regulatory scope.

Who Must Comply With FISMA Regulations

FISMA primarily applies to federal executive branch agencies and their information systems, both for the systems they operate and those they acquire. Every federal agency must implement an agency-wide information security program covering all systems under its operational control, regardless of whether those systems are managed internally or by third parties.

Contractors, vendors, service providers, and other non-federal entities that operate, support, or manage information systems on behalf of a federal agency are also within FISMA's scope. This includes cloud service providers hosting federal data, SaaS platforms processing federal information, managed service providers operating federal infrastructure, and software vendors whose applications handle federal system data. The compliance obligation flows through the supply chain—prime contractors must ensure subcontractors maintain appropriate security controls for any systems touching federal data.

Enterprise clients frequently impose FISMA-equivalent security requirements on vendors even when no federal contract exists. Organizations in healthcare, financial services, and defense-adjacent sectors often require vendors to demonstrate FISMA-aligned security programs as a condition of doing business. This creates practical compliance obligations for vendors serving regulated markets, regardless of direct federal contracting relationships.

Systems and Data Covered Under FISMA

FISMA applies to federal information systems, defined as systems used or operated by a federal agency, contractor, or other organization on behalf of an agency. Data from these programs must be stored on U.S. soil. Any system that stores, processes, or transmits federal information falls under FISMA requirements, regardless of whether that system is owned by the agency or provided by a third party.

This definition encompasses a broad range of infrastructure: agency-owned data centers, contractor-managed cloud environments, SaaS applications used for federal business processes, collaboration platforms handling federal communications, and third-party tools integrated with federal systems. Shared infrastructure creates particular complexity—if a multi-tenant platform serves both federal and commercial customers, the portions handling federal data require FISMA controls even if the underlying infrastructure serves mixed purposes.

Common gray areas that create compliance risk include development and staging environments containing copies of production data, backup systems storing federal information, logging platforms aggregating federal system telemetry, and administrative tools with privileged access to federal systems. Organizations often underestimate FISMA scope by focusing exclusively on production systems while neglecting supporting infrastructure that processes federal data. Proper system boundary definition and data flow mapping are essential to identify all systems requiring FISMA controls.

FISMA and NIST: How the Framework Works

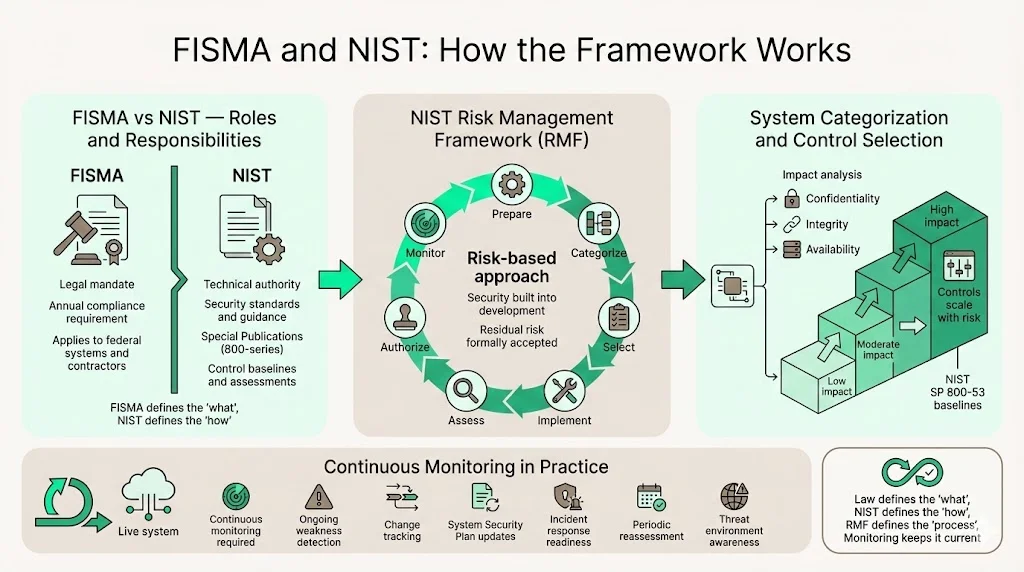

While FISMA sets the legal requirement for annual compliance, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is the government body responsible for developing the standards and policies that agencies use to ensure their systems, applications, and networks remain secure. FISMA establishes the mandate; NIST provides the technical implementation guidance through its Special Publications, particularly the 800-series documents that define security requirements, control baselines, and assessment procedures.The Risk Management Framework (RMF) is NIST's structured process for integrating security and risk management activities into the system development lifecycle. The RMF consists of seven steps: Prepare (organizational-level activities), Categorize (determine impact levels), Select (choose baseline controls), Implement (deploy controls), Assess (verify effectiveness), Authorize (accept residual risk), and Monitor (maintain ongoing awareness).

System categorization determines security requirements based on the potential impact of a security breach on confidentiality, integrity, and availability. Federal systems are categorized as Low, Moderate, or High impact using FIPS 199 standards. This categorization drives control selection—Low-impact systems require fewer controls than High-impact systems. NIST SP 800-53 outlines the suggested security controls for FISMA compliance, organized into control baselines corresponding to each impact level.

Continuous monitoring is a core FISMA requirement—agencies must continually monitor FISMA accredited systems to identify potential weaknesses, document changes in the System Security and Privacy Plan, and respond quickly to security incidents or data breaches. The RMF's Monitor step formalizes this expectation, requiring ongoing security status monitoring, change management, and periodic reassessment of security controls to ensure they remain effective as systems and threat environments evolve.

Core Cybersecurity Standards Under FISMA

FISMA emphasizes confidentiality, integrity, and availability, mandates annual reviews, and establishes specific requirements across multiple security domains. Federal systems must meet minimum security requirements defined in NIST SP 800-53, which organizes security and privacy controls into families covering access control, awareness and training, audit and accountability, configuration management, contingency planning, identification and authentication, incident response, maintenance, media protection, physical protection, risk assessment, security assessment, system and communications protection, and system and information integrity.

FISMA does not require an agency to implement every single control, but they must implement the controls relevant to their systems and their function. Control selection follows a tailoring process where agencies start with the baseline controls for their system's impact level, then add controls based on risk assessments and remove controls that are not applicable with documented justification.

Administrative controls include security planning, personnel security, risk management processes, and security awareness training. Technical controls cover access enforcement mechanisms, encryption requirements, intrusion detection and prevention, network segmentation, vulnerability scanning, and malware protection. Physical security controls address facility access, environmental protections, and media handling procedures.

Documentation requirements are extensive—documentation on the baseline controls used to protect a system must be kept in the form of a System Security and Privacy Plan. This is a key deliverable in the process of getting Authorization to Operate for a FISMA system. Organizations must maintain security control implementation documentation, assessment reports, plan of action and milestones for remediation, continuous monitoring strategies, and incident response procedures.

Risk Management and Information Assurance

FISMA requires a risk-based approach to information security—agencies must evaluate risks, implement controls proportionate to those risks, and continuously reassess as conditions change. System risk should be evaluated regularly to validate current security controls and to determine if additional controls are required. This risk management discipline extends throughout the system lifecycle, from initial design through decommissioning.

Threat modeling identifies potential attack vectors, threat actors, and exploitation scenarios relevant to each system. Vulnerability handling encompasses regular vulnerability scanning, patch management processes, compensating controls for vulnerabilities that cannot be immediately remediated, and tracking of remediation timelines. Organizations must maintain vulnerability management programs with documented procedures for identifying, classifying, remediating, and verifying vulnerabilities across all system components.

Risk acceptance occurs when senior leadership formally acknowledges residual risk after controls are implemented and determines that risk level is acceptable for continued operations. This authorization to operate (ATO) represents a formal determination that the system meets minimum security requirements and that remaining risks are understood and accepted. ATOs are time-limited—typically valid for three years—and require continuous monitoring to ensure security posture does not degrade during the authorization period.

Information assurance provides stakeholders with confidence that information systems protect data throughout its lifecycle and maintain appropriate levels of confidentiality, integrity, and availability. For vendors serving enterprise clients, demonstrable information assurance capabilities—documented controls, regular assessments, continuous monitoring, incident response readiness—build trust during procurement processes and reduce friction in security reviews.

Incident Response and Reporting Requirements

FISMA establishes specific incident response procedures for federal agencies, including requirements to detect, report, and respond to security incidents within defined timeframes. The 2014 modernization simplified existing FISMA reporting to eliminate inefficient or wasteful reporting while adding new reporting requirements for major information security incidents. Agencies must report major incidents to Congress, OMB, and DHS within prescribed timelines—typically within one hour for initial notification of major incidents.

Incident response procedures must include detection capabilities, classification and prioritization processes, containment and eradication procedures, recovery activities, and post-incident analysis. Federal agencies must coordinate incident response with CISA, which provides technical assistance and cross-agency threat intelligence. Contractors and service providers managing federal systems must follow incident notification procedures specified in their contracts, typically requiring immediate notification to the contracting agency and coordination with federal incident response teams.

Response readiness becomes a critical factor during vendor security reviews. Enterprise buyers evaluate whether vendors can detect incidents promptly, contain breaches effectively, preserve evidence for investigation, communicate clearly during crises, and conduct thorough post-incident analysis. Organizations with documented incident response plans, regular tabletop exercises, defined escalation procedures, and established communication channels demonstrate maturity that accelerates procurement decisions.

FISMA Compliance and IT Security Compliance Programs

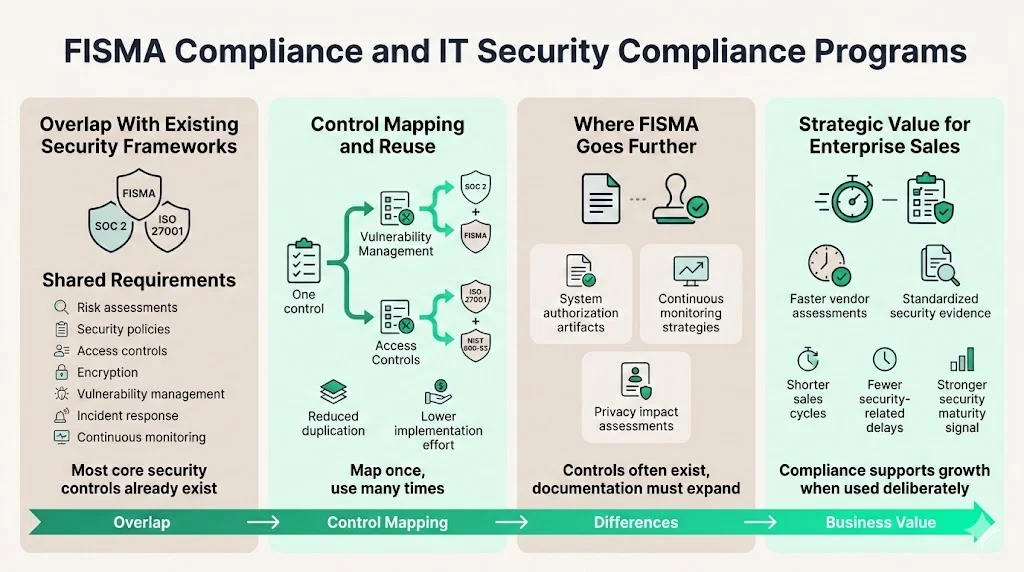

FISMA fits into broader IT security compliance efforts as a comprehensive framework addressing most aspects of information security governance. Organizations already maintaining SOC 2, ISO 27001, or similar certifications often find substantial overlap with FISMA requirements—both frameworks require risk assessments, documented security policies, access controls, encryption, vulnerability management, incident response capabilities, and continuous monitoring.

Control mapping reduces duplication by identifying where existing controls satisfy multiple framework requirements simultaneously. For example, a vulnerability management program implemented for SOC 2 compliance typically satisfies FISMA vulnerability handling requirements with minimal modification. Access control implementations meeting ISO 27001 requirements often align with NIST 800-53 access control families. Organizations can leverage existing security investments across multiple compliance obligations through careful control mapping and gap analysis.

Differences exist in documentation depth, assessment rigor, and specific technical requirements. FISMA typically requires more detailed system documentation than commercial frameworks, particularly around system authorization artifacts, continuous monitoring strategies, and privacy impact assessments. Organizations must supplement existing compliance programs with FISMA-specific documentation while leveraging common control implementations to minimize incremental effort.

Using compliance strategically supports enterprise sales cycles by demonstrating security maturity, reducing vendor assessment timelines, and providing standardized evidence for due diligence processes. Organizations with established compliance programs answer security questionnaires more efficiently, complete vendor assessments faster, and negotiate contracts with fewer security-related delays than organizations building security programs reactively during sales processes.

Common FISMA Compliance Gaps

Weak asset inventory and system boundaries create foundational compliance problems. Agencies and contractors struggle to maintain accurate inventories of hardware, software, data flows, and system interconnections—particularly in dynamic cloud environments where resources are provisioned automatically. Without complete asset visibility, organizations cannot properly scope security controls, monitor for unauthorized changes, or respond effectively to vulnerabilities affecting specific components.

Incomplete security control implementation occurs when organizations document controls in security plans without actually deploying them in operational environments. This "compliance manufacturing" approach satisfies documentation requirements while leaving systems fundamentally insecure. Common implementation gaps include incomplete log collection, insufficient network segmentation, inadequate encryption of data at rest, and access controls that fail to enforce least privilege principles.

Poor documentation and evidence tracking prevents organizations from demonstrating control effectiveness during audits. Many organizations implement reasonable security measures but lack documented procedures, assessment results, or change tracking to prove controls operate consistently. System Security and Privacy Plans grow stale as systems evolve, continuous monitoring data remains siloed in security tools rather than centralized for analysis, and remediation tracking occurs informally rather than through structured plan of action and milestones processes.

Gaps in incident response testing reveal themselves when actual incidents occur. Organizations maintain incident response plans that have never been exercised through tabletop scenarios or simulation exercises. Escalation procedures remain untested, forensic data sources prove incomplete, and communication channels fail under stress. Regular incident response exercises identify procedural gaps, validate technical capabilities, and build organizational muscle memory for crisis response.

Vendor and third-party risk blind spots emerge when organizations focus exclusively on directly-managed systems while overlooking security risks introduced through supply chain relationships. Contractors using subcontractors, SaaS platforms integrating with federal systems, and open-source components embedded in applications all introduce risk that requires assessment and monitoring. Comprehensive third-party risk management programs inventory all vendor relationships, assess security posture based on data sensitivity and system criticality, require contractual security obligations, and monitor vendor security posture continuously.

FISMA Audits and Assessments

Program officials and agency heads must conduct annual security reviews in order to obtain a FISMA certification. These assessments evaluate whether agencies maintain effective information security programs and comply with FISMA requirements. Independent assessors—typically Inspectors General for federal agencies or third-party assessment organizations for contractors—conduct annual FISMA evaluations using standardized metrics developed by OMB and DHS.

The assessment process examines security controls across nine security domains: risk management, configuration management, identity and access management, data protection and privacy, security training, information security continuous monitoring, incident response, contingency planning, and contractor systems. Assessors review documentation, interview personnel, observe processes, and test technical controls to determine both implementation completeness and operational effectiveness.

Annual reviews combine with continuous monitoring to provide ongoing security visibility. Continuous monitoring involves automated security status reporting, vulnerability scanning, configuration management tracking, and security event analysis. Organizations maintain continuous monitoring strategies that define what gets monitored, how frequently, who receives reports, and what thresholds trigger escalation. This continuous monitoring data supports annual assessments by providing longitudinal evidence of control effectiveness.

Audit outcomes affect enterprise procurement directly. Poor FISMA assessment results may preclude agencies from acquiring new systems, limit authorization durations, or trigger increased oversight from OMB and DHS. For contractors, FISMA compliance gaps discovered during agency assessments can result in contract remediation requirements, delayed payments, or contract termination for material security failures. Enterprise buyers reviewing vendors consider FISMA assessment results—or equivalent third-party security assessments—as indicators of security program maturity and operational reliability.

Why FISMA Regulations Matter to Enterprise Vendors

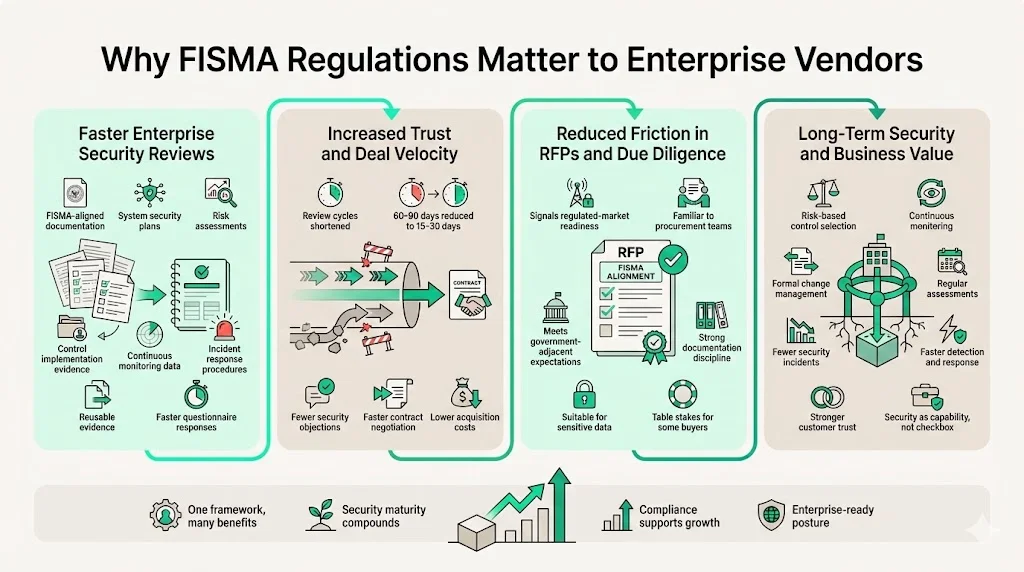

FISMA readiness shortens security reviews by providing standardized documentation and evidence that directly addresses common enterprise security questions. Organizations with FISMA-aligned security programs can respond to vendor security questionnaires more efficiently because they maintain the documentation enterprises require—system security plans, risk assessments, control implementation evidence, continuous monitoring data, and incident response procedures. This documentation exists in structured formats that map cleanly to enterprise security requirements.

Impact on enterprise trust and deal velocity is substantial. Security reviews that might require 60-90 days for organizations building documentation reactively compress to 15-30 days when vendors maintain FISMA-ready security programs. Procurement teams gain confidence faster when vendors demonstrate mature security practices aligned with recognized frameworks. This confidence accelerates contract negotiations and reduces security-related deal delays that extend sales cycles and increase customer acquisition costs.

Reducing friction during RFPs and due diligence creates competitive advantage in enterprise sales. FISMA compliance signals to procurement teams that a vendor understands regulated environment requirements, maintains documentation disciplines expected in government and government-adjacent markets, and operates security programs at maturity levels required for sensitive data handling. Organizations pursuing federal contracts or selling to buyers with federal relationships find FISMA alignment often becomes table stakes for consideration.

Long-term value of structured security programs extends beyond individual compliance frameworks. The disciplines FISMA requires—risk-based control selection, continuous monitoring, formal change management, regular assessments—build organizational capabilities that improve security outcomes independent of compliance obligations. Organizations operating mature security programs experience fewer security incidents, detect breaches faster when they occur, recover more efficiently from security events, and maintain customer trust more effectively than organizations treating security as a checkbox exercise.

Conclusion

FISMA regulations establish information security standards that reach far beyond federal agencies into contractor operations and enterprise vendor relationships. Organizations selling into regulated environments encounter FISMA-derived requirements regardless of direct federal contracting relationships—enterprise buyers in healthcare, finance, and defense-adjacent sectors routinely impose FISMA-equivalent security controls as procurement prerequisites. This reality makes FISMA literacy essential for vendors pursuing enterprise clients with regulatory exposure or government connections.

Preparing early rather than reacting late produces better security outcomes at lower total cost. Organizations building FISMA-aligned security programs proactively develop capabilities that support multiple compliance frameworks, accelerate enterprise sales cycles, and improve actual security posture. Reactive approaches—scrambling to meet FISMA requirements during active procurement processes—result in rushed implementations, incomplete documentation, and security programs that satisfy auditors on paper while leaving organizations fundamentally insecure.

Strong security and compliance habits support growth by reducing friction in enterprise sales, building customer trust through demonstrated security maturity, and creating operational efficiencies that scale as organizations expand. Compliance certifications are outcomes of continuous security operations, not projects with defined end dates. Organizations treating security as an operational discipline rather than a periodic compliance exercise build sustainable competitive advantages in markets where security assurance drives purchasing decisions.

FAQs

1. Who must comply with FISMA regulations?

FISMA primarily applies to federal executive branch agencies and their information systems, both for the systems they operate and those they acquire. Contractors, vendors, service providers, and other non-federal entities that operate, support, or manage information systems on behalf of a federal agency are also within FISMA's scope. This includes cloud providers, SaaS platforms, managed service providers, and any organization processing federal data under contract.

2. What systems fall under FISMA?

Any system that stores, processes, or transmits federal information falls under FISMA requirements. This encompasses agency-owned infrastructure, contractor-managed cloud environments, third-party applications handling federal data, and supporting systems including development environments, backup systems, logging platforms, and administrative tools with access to federal systems. System boundaries extend to all infrastructure components that handle federal data regardless of ownership.

3. How does FISMA relate to NIST?

While FISMA sets the legal requirement for annual compliance, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is the government body responsible for developing the standards and policies that agencies use to ensure their systems, applications, and networks remain secure. FISMA establishes the mandate; NIST provides implementation guidance through Special Publications including the Risk Management Framework and SP 800-53 security control baselines.

4. What are common FISMA compliance gaps?

Common gaps include weak asset inventory and system boundary definition, incomplete security control implementation, poor documentation and evidence tracking, insufficient incident response testing, and vendor risk management blind spots. Organizations often document controls without implementing them operationally, maintain stale security plans that no longer reflect system reality, and overlook supply chain risks introduced through third-party relationships.

5. How often are FISMA audits required?

Program officials and the head of each agency must conduct annual reviews of information security programs, with the intent of keeping risks at or below specified acceptable levels. These annual assessments combine with continuous monitoring requirements—organizations must maintain ongoing security status visibility, vulnerability tracking, and incident detection throughout authorization periods rather than treating compliance as an annual event.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)