Most organizations approach risk management as a procedural checklist—documenting controls, collecting evidence, preparing for audits. This creates a fundamental gap between paper-based compliance and actual accountability for security risk. That gap becomes apparent when incidents occur or when systems face rigorous regulatory scrutiny, and no single executive has formally accepted responsibility for operating the system at a defined risk level.

What is an AO?

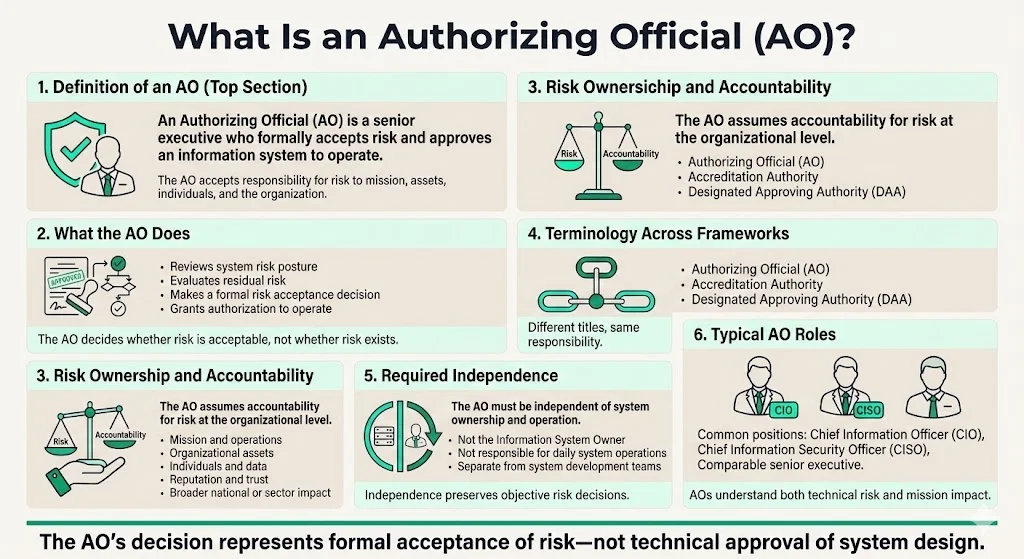

An Authorizing Official (AO) is a senior federal official or executive with the authority to formally assume responsibility for operating an information system at an acceptable level of risk to organizational operations (including mission, functions, image, or reputation), organizational assets, individuals, other organizations, and the Nation.

The AO role is synonymous with Accreditation Authority and has previously been referred to as Designated Approving Authority (DAA) in certain regulatory contexts. While the terminology varies across frameworks and sectors, the core function remains consistent: a designated senior executive formally accepts residual risk and grants permission for an information system to operate.

Critical distinction: the AO is never the information system owner (ISO) to prevent any conflicts of interest. This separation ensures objectivity in risk assessment and maintains governance integrity. The AO must be organizationally independent of the system development, ownership, and day-to-day operations—typically a Chief Information Officer (CIO), Chief Information Security Officer (CISO), or comparable executive who understands both technical risk and mission impact without direct operational responsibility for the system in question.

Why AO Matters: Role in Security and Compliance

1) Risk Acceptance and Accountability

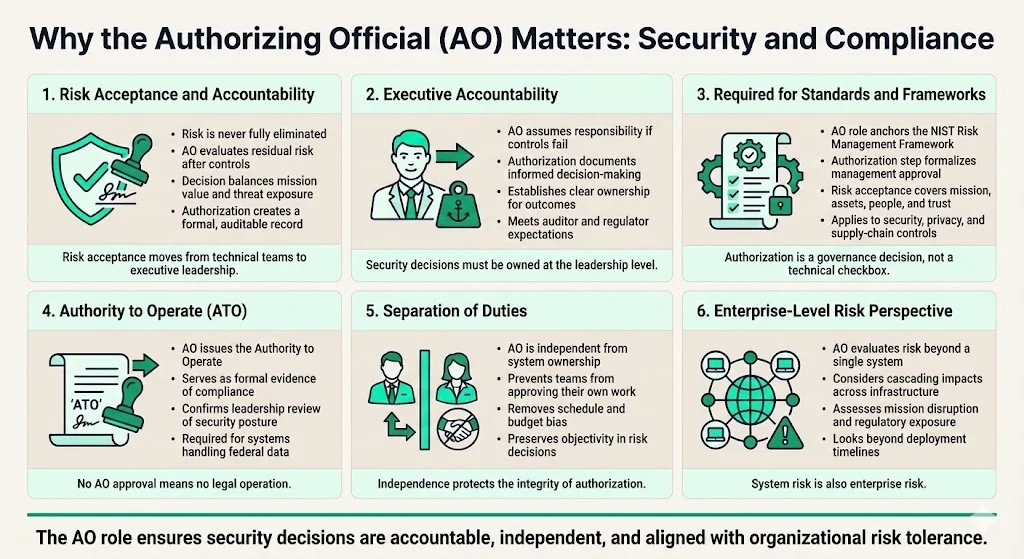

Risk can never be completely eliminated from an information system, so an AO weighs the risk-to-benefit ratio of a system to decide its authorization status. The AO's primary responsibility centers on evaluating whether residual risk—the risk remaining after implementing security controls—falls within acceptable organizational tolerances given the system's mission value, operational dependencies, and threat landscape.

This is not theoretical risk management. The AO formally assumes accountability for adverse outcomes if implemented controls fail or threats materialize. By signing an authorization decision, the AO creates an auditable record demonstrating that a senior executive reviewed security evidence, understood residual vulnerabilities, and made an informed decision that operating the system serves organizational interests despite remaining risk.

This formal declaration establishes clear lines of accountability that extend beyond technical teams to executive leadership—exactly what regulators, auditors, and business partners demand when evaluating an organization's security posture.

2) Compliance with Standards and Frameworks

The AO role is foundational to the NIST Risk Management Framework (RMF), which defines how federal agencies and organizations handling federal data must approach information security. Through the "authorize" step of the RMF, the AO issues an official management decision to authorize operation of an information system and explicitly accept the risk to agency operations (including mission, functions, image, or reputation), agency assets, individuals, other organizations, and the Nation based on the implementation of an agreed-upon set of security and privacy controls.

The AO's authorization decision—formalized as an Authority to Operate (ATO)—serves as regulatory evidence that the system meets required security, privacy, and supply chain risk management controls as mandated by applicable standards. This authorization represents more than technical compliance; it demonstrates that executive leadership has reviewed the system's security architecture, assessed its vulnerabilities against organizational risk tolerance, and formally sanctioned its operation.

For organizations subject to federal oversight or contractual requirements tied to NIST frameworks, securing AO approval is non-negotiable. Without it, systems cannot legally process federal information or integrate with government networks.

3) Separation of Duties and Independence

The mandatory separation between AO and system owner prevents the conflict of interest that arises when technical teams assess their own work. System owners have operational and often budgetary incentives to declare systems ready for deployment. Requiring an independent executive—removed from development pressures and project timelines—to review security evidence and formally accept risk introduces governance rigor that protects organizational interests.

This independence ensures the authorization decision reflects genuine risk assessment rather than scheduled accommodation. The AO evaluates security posture through an enterprise lens, considering how system vulnerabilities could cascade across interconnected infrastructure, impact mission-critical operations, or expose the organization to regulatory penalties.

How AO Fits Into the Compliance and Authorization Process

The RMF structures information system authorization through six sequential steps: Prepare, Categorize, Select, Implement, Assess, Authorize, and Monitor. The AO's role concentrates in the Authorize step, though their involvement begins earlier through oversight of the authorization strategy and risk management approach.

Before authorization, the AO receives a comprehensive authorization package—a collection of security documentation that includes:

- System Security Plan (SSP): Describes the system architecture, security boundaries, control implementation, and operational environment

- Security Assessment Report (SAR): Documents independent testing and evaluation of implemented controls, identifying vulnerabilities and control deficiencies

- Plan of Action and Milestones (POA&M): Details remediation timelines for identified vulnerabilities, risk mitigation strategies, and accountability assignments

- Risk Assessment Report: Quantifies threats, vulnerabilities, likelihood of exploitation, and potential impact to organizational operations

- Privacy Impact Assessment: Evaluates data handling practices, personally identifiable information (PII) protections, and regulatory compliance for systems processing sensitive data

The AO reviews this package—often supported by an Authorizing Official Designated Representative (AODR) who conducts detailed technical review and provides authorization recommendations—then issues one of several possible decisions:

- Authorization to Operate (ATO): Full approval for system operation, typically valid for three years with conditions for continuous monitoring and periodic reassessment

- Interim Authorization to Operate (IATO): Temporary authorization granted by an authorizing official for an information system to process information based on preliminary results of a security evaluation of the system

- Denial of Authorization: System does not meet minimum security requirements; operation is prohibited until deficiencies are remediated

The ATO decision document includes the conditions under which the ATO is valid, as well as an expiration date. These conditions often mandate specific compensating controls, impose operational restrictions, or require accelerated remediation of identified vulnerabilities.

Authorization is not a terminal state. The AO regularly reviews data accumulated from security monitoring reports to inform ongoing authorization decisions. Systems undergo continuous monitoring with automated vulnerability scanning, configuration management verification, and incident tracking. Significant system changes—architecture modifications, new interconnections, changes to data sensitivity—trigger reauthorization requirements, ensuring the AO's risk acceptance remains valid as the system evolves.

When and Where AO is Relevant—Who Uses It

The AO model originated within federal government agencies operating under FISMA (Federal Information Security Management Act) requirements and OMB Circular A-130 mandates. Federal agencies must designate AOs for all information systems processing government data, making this role ubiquitous across civilian agencies, defense organizations, and intelligence community systems.

In the Department of Defense (DoD) Authority to Operate (ATO) process, Authorizing Officials assume responsibility for operating an information system at an acceptable level of risk to agency operations. This role is vital to the ATO process, and it is important for software companies seeking an ATO to have an understanding of the responsibilities and priorities of DoD AOs.

Beyond direct government operations, the AO framework extends to:

- Government contractors and cloud service providers: Organizations providing software, infrastructure, or managed services to federal agencies must obtain ATO through an AO-driven authorization process. FedRAMP (Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program) authorizations rely on AO decisions at the Joint Authorization Board or agency level.

- Regulated industries handling federal data: Healthcare organizations managing Medicare/Medicaid data, financial institutions processing federal payments, and educational institutions receiving federal funding often adopt AO-equivalent roles to satisfy regulatory accountability requirements.

- Enterprises with mature security governance: Private sector organizations—particularly those in financial services, critical infrastructure, or handling sensitive customer data—increasingly implement AO-style authorization processes internally. Designating a senior executive to formally accept system risk and sign authorization decisions creates governance rigor that strengthens security posture and satisfies audit requirements.

For companies selling B2B software or infrastructure to enterprise clients, understanding the AO model provides strategic advantage. Large organizations evaluating vendor security increasingly expect authorization evidence mirroring government standards—documented risk assessments, independent security testing, executive sign-off on residual risk. Vendors who implement AO-aligned authorization internally can demonstrate security maturity that differentiates their offerings during procurement evaluations.

Implications for Enterprises Selling to Large Clients

Organizations pursuing contracts with government agencies or large regulated enterprises encounter AO-driven authorization requirements throughout the sales cycle and post-deployment operations. Understanding AO expectations shapes how vendors structure security programs, document compliance, and engage with client procurement and security teams.

When enterprise clients evaluate vendor security, they assess whether your organization has implemented governance structures equivalent to their internal standards. If your prospective client operates under an AO model—common in government, defense, financial services, and healthcare—they expect vendors to demonstrate:

- Executive accountability for risk: Evidence that senior leadership formally reviews and accepts residual security risks in your systems, not just technical teams asserting compliance

- Independent security assessment: Third-party testing and validation of security controls, mirroring the independent assessor role in government authorizations

- Comprehensive authorization documentation: Security architecture documentation, assessment reports, vulnerability tracking, and remediation plans comparable to government authorization packages

- Continuous monitoring and reauthorization triggers: Processes for detecting security changes, assessing impact, and escalating significant modifications for authorization review

Vendors who implement AO-aligned authorization workflows internally reduce friction during client security reviews. When client security teams request authorization evidence, vendors operating with AO-style governance can provide documentation that directly maps to client expectations—system security plans, independent assessment reports, executive authorization decisions, continuous monitoring outputs.

This alignment accelerates procurement cycles, reduces redundant security questionnaires, and builds client confidence that your organization manages security with rigor comparable to their internal standards. For vendors pursuing government contracts specifically, understanding AO responsibilities and decision criteria is non-negotiable—your system will ultimately require AO approval at the client agency, and demonstrating familiarity with the authorization process signals operational readiness.

Common Misconceptions and Clarifications

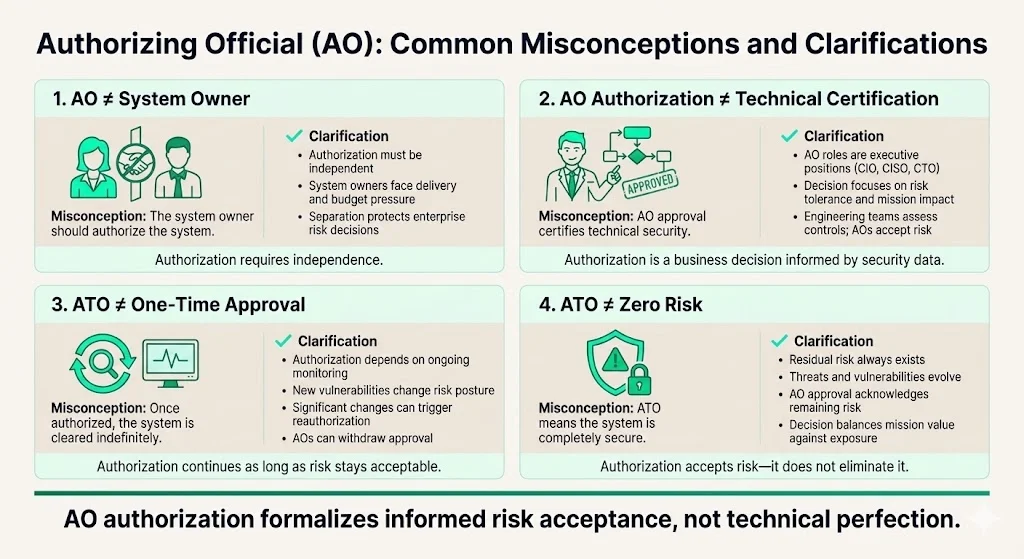

1) AO and system owner are not interchangeable roles. The most persistent misconception is that whoever owns or operates a system should authorize it. This violates fundamental separation-of-duties principles. System owners have operational and budgetary pressures to deploy systems; requiring independent executive review ensures authorization decisions reflect enterprise risk tolerance rather than project schedules.

2) AO authorization is not a technical certification. Authorizing Officials are high-ranking members within an agency such as Chief Information Officers (CIO), Chief Information Security Officers (CISO), or Chief Technology Officer (CTO). While AOs must understand information security concepts, their role centers on risk management and business judgment, not technical implementation. AOs evaluate whether security controls adequately protect organizational operations given mission requirements and threat environment—a strategic decision requiring executive perspective rather than engineering expertise.

3) Authorization is not a one-time approval gate. Organizations frequently treat ATO as a project milestone—achieve authorization, then shift focus to operations. In practice, authorization requires continuous validation. Security monitoring detects control failures, vulnerability management identifies new weaknesses, and system changes introduce new risks. AOs review monitoring data regularly and can withdraw authorization if security posture degrades or if unauthorized changes occur. Effective authorization is an ongoing program, not a discrete project.

4) AO approval does not guarantee zero risk. Some stakeholders interpret ATO as certification that a system is completely secure. This fundamentally misunderstands risk management. Every information system contains residual risk—vulnerabilities that remain after implementing controls, threats that controls cannot fully mitigate, and unknown risks that emerge as attack techniques evolve. The AO's decision acknowledges this reality: the system presents acceptable risk given its mission value and implemented protections. Authorization formalizes informed risk acceptance, not risk elimination.

Conclusion

The Authorizing Official serves as the linchpin in risk-based security authorization—a senior executive who formally accepts responsibility for operating an information system at a defined risk level after reviewing comprehensive security evidence and assessing whether residual vulnerabilities fall within organizational tolerance. This role transforms security from a technical checklist into executive accountability, creating clear responsibility for risk decisions and ensuring systems operate under informed authorization rather than assumed compliance.

For organizations subject to federal regulations or contractual requirements tied to NIST frameworks, designating an AO and following structured authorization processes is mandatory. But the AO model provides value beyond regulatory compliance. By requiring independent executive review of security posture, formal documentation of risk decisions, and continuous validation of authorization conditions, the AO framework creates governance discipline that strengthens security programs and demonstrates maturity to auditors, regulators, and enterprise clients.

Enterprise-facing companies—particularly those selling to government agencies, regulated industries, or security-conscious organizations—benefit from understanding AO-driven authorization. Implementing parallel authorization processes internally, documenting security decisions through AO-aligned frameworks, and demonstrating executive accountability for risk positions vendors as credible partners who manage security with rigor comparable to client expectations. This is not performative compliance. It reflects operational discipline that produces genuine security outcomes while satisfying the authorization requirements that gate access to high-value contracts.

FAQs

1) What does "AO" actually stand for?

AO stands for Authorizing Official—a senior executive who formally approves information system operation and explicitly accepts residual security risk on behalf of the organization.

2) Is AO the same as the system owner (ISO)?

No. The AO must be organizationally independent of the system owner to prevent conflicts of interest. System owners manage day-to-day operations; AOs provide independent risk assessment and authorization decisions.

3) What criteria does an AO use to decide whether to approve a system?

AOs review authorization packages containing system security plans, independent assessment reports, risk assessments, and remediation plans. They evaluate whether implemented security controls adequately mitigate threats given the system's mission value, data sensitivity, operational environment, and organizational risk tolerance. The decision balances security posture against business requirements.

4) What happens after AO approval?

The system operates under an Authorization to Operate (ATO), typically valid for three years. Systems undergo continuous monitoring—automated vulnerability scanning, configuration validation, incident tracking—with regular reporting to the AO. Significant system changes, control failures, or emerging threats may trigger reauthorization requirements. The AO can withdraw authorization if security posture degrades.

5) Is AO relevant only for government agencies?

While AO originates from federal frameworks, the model extends to government contractors, cloud service providers, regulated industries, and private enterprises handling sensitive data. Organizations pursuing government contracts must navigate AO-driven authorization. Companies in regulated sectors increasingly adopt AO-equivalent roles internally to demonstrate security governance maturity.

6) Can AO's decision be challenged or reversed?

Yes. If continuous monitoring detects control failures, new vulnerabilities emerge, or system changes introduce unacceptable risk, the AO can withdraw authorization, impose additional controls, or require remediation before continued operation. Reauthorization cycles—typically every three years—provide formal reassessment checkpoints where AOs can decline renewal if security posture has degraded.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)