The Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA) establishes mandatory security requirements for federal information systems and the organizations that interact with them. For enterprise technology vendors, cloud service providers, and security solution companies pursuing federal contracts, FISMA compliance represents both a legal obligation and a competitive differentiator—yet many organizations misunderstand the depth of implementation required beyond basic documentation.

FISMA matters because it governs how federal agencies and their contractors must secure sensitive government data. Any organization storing, processing, or transmitting federal information operates within FISMA's scope, facing rigorous requirements for risk management, security controls, continuous monitoring, and incident reporting. This isn't performative compliance—FISMA mandates operational security disciplines designed to protect critical government systems from sophisticated cyber threats.

This definition clarifies what FISMA requires, who it applies to, how it integrates with broader cybersecurity frameworks like NIST standards, and why understanding FISMA's requirements proves essential for companies operating in the federal marketplace.

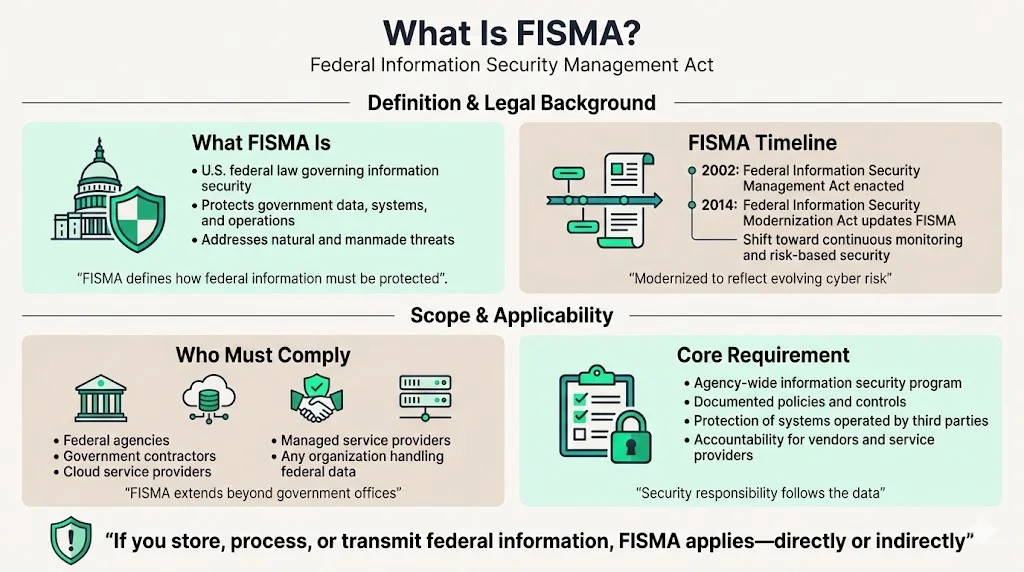

What Is FISMA?

Definition and BackgroundThe Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA) is United States federal law that defines a comprehensive framework to protect government information, operations, and assets against natural and manmade threats. The original FISMA was Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 (Public Law 107-347 (Title III); December 17, 2002), in the E-Government Act of 2002. The Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014 amends the Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 (FISMA).

The act requires each federal agency in the US government to develop, document, and implement an agency-wide information security program to protect sensitive data and information systems that support the operations and assets of the agency, including those provided or managed by another agency, third-party vendor, or service provider. FISMA applies not only to federal agencies themselves but extends to contractors, cloud providers, managed service providers, and any organization that stores, processes, or transmits federal data.

Why FISMA Exists

FISMA has brought attention within the federal government to cybersecurity and explicitly emphasized a "risk-based policy for cost-effective security." The legislation emerged from recognition that federal information systems face persistent, sophisticated cyber threats requiring standardized security practices across all agencies and their supporting organizations. Prior to FISMA, inconsistent security approaches across federal agencies created vulnerabilities that adversaries could exploit.

This law has been amended by the Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014 (sometimes called FISMA Reform), passed in response to the increasing amount of cyber attacks on the federal government. The 2014 modernization reflected evolving threat landscapes, strengthened the use of continuous monitoring in systems, increased focus on the agencies for compliance and reporting that is more focused on the issues caused by security incidents.

How It Works (High Level)

FISMA requires the head of each Federal agency to provide information security protections commensurate with the risk and magnitude of the harm resulting from unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption, modification, or destruction of information and information systems. Rather than prescriptive technical requirements, FISMA establishes a risk-based framework where organizations categorize systems by impact level, implement appropriate security controls, continuously monitor effectiveness, and report security posture to oversight authorities.

FISMA 2002 requires each federal agency to develop, document, and implement an agency-wide program to provide information security for the information and systems that support the operations and assets of the agency, including those provided or managed by another agency, contractor, or other sources. This places responsibility on agency leadership to establish comprehensive security programs—not merely comply with checklists—that integrate risk management into operational decision-making.

Agencies must notify Congress of major security incidents within seven days after there is a reasonable basis to conclude that a major incident has occurred. This incident reporting requirement ensures accountability and transparency when security controls fail, creating pressure for agencies to maintain genuine security posture rather than documentation theater.

How FISMA Fits into the Federal Security Framework

Relationship to NIST and Security Standards

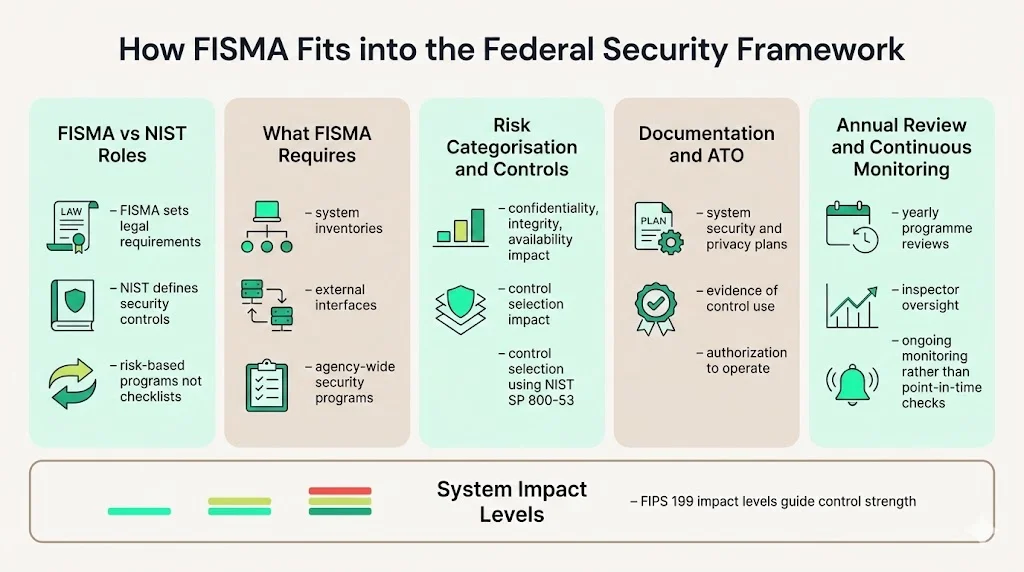

While FISMA sets the legal requirement for annual compliance, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is the government body responsible for developing the standards and policies that agencies use to ensure their systems, applications, and networks remain secure. Understanding this distinction proves critical: FISMA defines what must be achieved—comprehensive information security programs with documented risk management—while NIST publications like Special Publication 800-53 specify how to achieve those outcomes through detailed control catalogs.

Per FISMA, NIST is responsible for developing standards, guidelines, and associated methods and techniques for providing adequate information security for all agency operations and assets, excluding national security systems. Organizations often conflate FISMA compliance with implementing NIST controls, but The suite of NIST information security risk management standards and guidelines is not a 'FISMA Compliance checklist.' Instead, NIST provides the technical framework agencies use to fulfill FISMA's legislative mandate for risk-based security programs.

Core Components of FISMA

According to FISMA, the head of each agency shall develop and maintain an inventory of major information systems (including major national security systems) operated by or under the control of such agencies. This inventory requirement extends to identifying interfaces between systems, including external connections to networks not under agency control—a recognition that security boundaries extend beyond organizational perimeters.

FISMA compliance requires systematic risk categorization, where agencies evaluate potential impact of confidentiality, integrity, or availability compromises. Organizations must meet the minimum security requirements by selecting the appropriate security controls and assurance requirements as described in NIST Special Publication 800-53, "Recommended Security Controls for Federal Information Systems".

Documentation on the baseline controls used to protect a system must be kept in the form of a System Security and Privacy Plan (SSPP). This is a key deliverable in the process of getting Authorization to Operate (ATO) for a FISMA system. The System Security Plan functions as both implementation blueprint and evidence artifact, documenting how specific controls address identified risks for each information system.

A key requirement of FISMA is that program officials, and the head of each agency, must conduct annual reviews of information security programs, with the intent of keeping risks at or below specified acceptable levels. These annual reviews, conducted by chief information officers and independently evaluated by inspectors general, create accountability mechanisms ensuring security programs remain effective as threats evolve.

Continuous monitoring represents a fundamental FISMA requirement often misunderstood by organizations treating compliance as annual certification cycles. Agencies must continually monitor FISMA accredited systems to identify potential weaknesses. Continuous monitoring will also enable agencies to respond quickly to security incidents or data breaches. This ongoing assessment replaces outdated "snapshot" compliance approaches with sustained security operations.

Classification of Systems

All information and information systems should be categorized based on the objectives of providing appropriate levels of information security according to a range of risk levels. FISMA uses Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) 199 to establish three impact levels—Low, Moderate, and High—based on potential harm from compromised confidentiality, integrity, or availability.

This categorization determines which security controls organizations must implement. Systems handling highly sensitive federal information require more rigorous controls than systems with limited impact potential. The categorization process requires understanding both the types of information processed and the operational significance of system availability—a nuanced risk assessment that many organizations oversimplify during initial compliance efforts.

Use Cases: Who Needs to Care About FISMA

A. Federal Agencies

All executive branch agencies operate under FISMA's jurisdiction. FISMA requires agencies to report the status of their information security programs to OMB and requires Inspectors General (IG) to conduct annual independent assessments of those programs. Agency chief information officers bear direct responsibility for establishing, documenting, and maintaining information security programs that protect federal operations.

FISMA 2014 codifies the Department of Homeland Security's role in administering the implementation of information security policies for federal Executive Branch civilian agencies, overseeing agencies' compliance with those policies, and assisting OMB in developing those policies. This creates a governance structure where OMB sets policy, DHS provides implementation oversight, and individual agencies execute security programs under independent inspector general assessment.

B. Contractors and Vendors

FISMA's scope explicitly extends beyond federal employees to encompass any entity operating federal information systems or handling federal data. Cloud service providers hosting federal applications, software vendors whose products process federal information, systems integrators implementing federal IT infrastructure, and managed service providers operating federal networks all fall within FISMA's requirements.

For enterprise technology vendors, FISMA compliance often becomes a contract prerequisite. Federal procurement processes increasingly require vendors to demonstrate FISMA-aligned security controls before contract award, particularly for systems categorized as Moderate or High impact. Organizations lacking documented FISMA compliance capabilities face systematic exclusion from federal opportunities regardless of technical capabilities.

C. Other Entities

State and local government agencies receiving federal funding frequently encounter FISMA-aligned requirements in grant conditions. While not directly subject to FISMA as federal law, these entities must often implement equivalent controls to maintain federal funding streams—effectively extending FISMA's influence throughout the broader public sector.

D. Enterprise Tech Sellers

Enterprise platform vendors—particularly those offering security tools, cloud infrastructure, data platforms, or enterprise software—must understand FISMA to compete in federal markets. Federal buyers evaluate vendors not just on product capabilities but on demonstrated understanding of federal security requirements, risk management frameworks, and authorization processes.

Organizations positioning themselves as federal-ready vendors need documented security control implementations, evidence collection processes, and authorization artifacts that align with FISMA expectations. This requires moving beyond generic "compliance" claims to demonstrate specific understanding of System Security Plans, continuous monitoring requirements, and ATO processes that federal buyers recognize as genuine preparedness rather than marketing language.

FISMA Compliance: Step-by-Step

Basic Compliance Requirements

FISMA compliance begins with comprehensive system inventory. The identification of information systems in an inventory under this subsection shall include an identification of the interfaces between each such system and all other systems or networks, including those not operated by or under the control of the agency. This requires documenting not only systems under direct control but also external connections, data flows, and dependencies on third-party services.

Organizations must categorize each information system using FIPS 199 standards, evaluating potential impact to confidentiality, integrity, and availability. This categorization determines baseline security control requirements from NIST SP 800-53. FISMA does not require an agency to implement every single control, but they must implement the controls relevant to their systems and their function. This tailoring process requires documented risk-based decisions justifying control modifications.

Risk assessments provide the foundation for security control selection and implementation decisions. These assessments evaluate threats, vulnerabilities, likelihood of exploitation, and potential impact—producing risk scores that guide control prioritization and resource allocation.

System Security Plans document implemented controls, implementation details, control effectiveness, and residual risks for each information system. NIST SP-800-18 introduced the concept of a system security plan, a living document requiring periodic review, modification, plans of action, and milestones for implementing security controls. These plans serve as both implementation blueprints and audit evidence.

Authorization to Operate represents formal acceptance of residual risk by authorizing officials after security control assessment. During the process, the system security plan is analyzed, updated, and then accepted by a certification agent, confirming the security controls described are consistent with FIPS 199 and FIPS 200. ATO decisions authorize system operation for defined periods, typically three years, conditioned on sustained control effectiveness.

Monitoring and Incident Reporting

Continuous monitoring activities include configuration management, control of information system components, the security impact analysis of changes to the system (like security ratings), ongoing assessment of security controls, and status reporting. This ongoing assessment replaces periodic "snapshot" audits with sustained visibility into security posture changes.

Agencies must submit an annual report regarding major incidents to OMB, DHS, Congress, and the Comptroller General. This incident reporting creates accountability for security program effectiveness and provides transparency into federal cybersecurity posture at the policy level.

Ongoing Risk Management

FISMA emphasizes continuous risk management rather than point-in-time compliance milestones. FISMA requires program officials and agency heads to conduct annual security reviews to ensure security controls are sufficient and risk is sufficiently mitigated. These reviews assess whether implemented controls remain effective as threats evolve, systems change, and organizational risk tolerance shifts.

Large changes should trigger an updated risk assessment and may need to be recertified. This ensures Authorization to Operate decisions remain valid as systems evolve—preventing security posture drift where documented controls diverge from operational reality.

Why FISMA Matters for Enterprise Clients

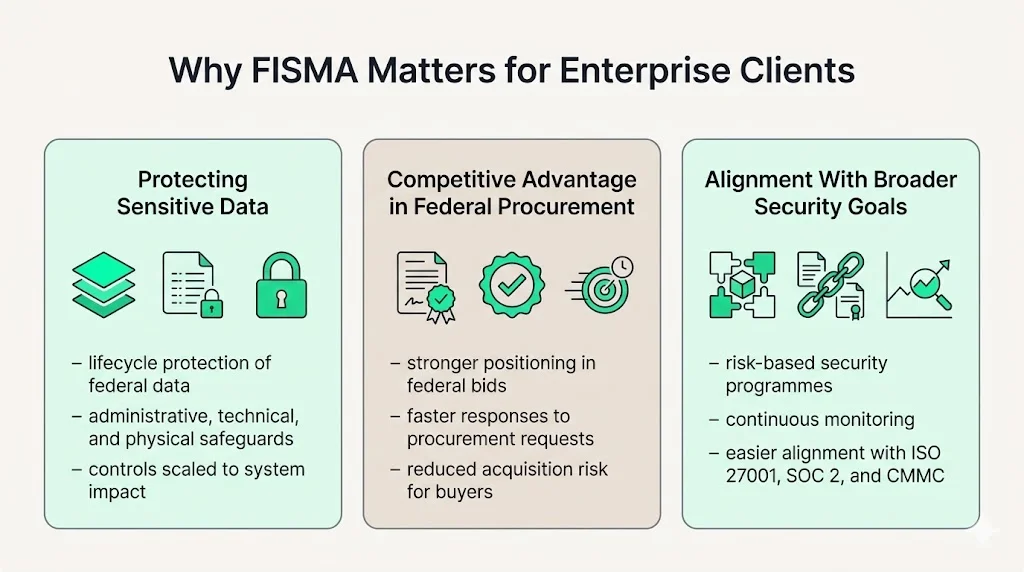

A. Protecting Data

FISMA establishes rigorous requirements for protecting federal information throughout its lifecycle. Organizations handling federal data must implement administrative, technical, and physical safeguards proportionate to system impact categorization—creating defense-in-depth approaches that address threats at multiple layers.

Federal information systems often contain personally identifiable information, law enforcement data, national security information, or other sensitive data requiring protection from unauthorized disclosure, modification, or destruction. FISMA's risk-based framework ensures security controls scale appropriately to data sensitivity and operational criticality.

B. Competitive Advantage

For private-sector companies who do business with federal agencies, FISMA compliance can provide a leg up over other organizations when vying for federal contracts. Federal procurement increasingly evaluates cybersecurity capabilities during source selection, making documented FISMA compliance a competitive differentiator rather than merely a threshold requirement.

Organizations that maintain continuous FISMA readiness respond faster to federal procurement opportunities, provide more credible security documentation, and demonstrate operational security maturity that federal buyers recognize as reducing acquisition risk. Competitors lacking this preparedness face longer authorization timelines, higher compliance costs, and increased probability of disqualification during technical evaluation.

C. Alignment With Broader Cybersecurity Goals

Many organizations adopt FISMA-aligned security frameworks even for non-federal operations because the risk management approach, control catalog, and continuous monitoring requirements establish comprehensive security programs applicable across diverse operating environments. FISMA's emphasis on documented risk assessments, tailored control implementation, and sustained effectiveness assessment provides a mature security program structure that scales beyond federal compliance.

Organizations implementing FISMA-aligned programs often find alignment with other frameworks—ISO 27001, SOC 2, CMMC—becomes simpler because fundamental risk management disciplines, control documentation practices, and evidence collection processes translate across compliance regimes.

FISMA vs. Other Frameworks

FISMA and NIST

FISMA represents legislative mandate; NIST provides implementation guidance. This distinction proves critical: Compliance with applicable laws, regulations, executive orders, directives, etc. is a byproduct of implementing a robust, risk-based information security program. Organizations treating NIST publications as compliance checklists miss FISMA's fundamental requirement for risk-based security programs that produce defensible risk management outcomes.

NIST develops standards and guidelines, such as minimum security requirements and controls needed for FISMA compliance. NIST SP 800-53 Rev. 5: Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations defines the controls needed for FISMA compliance. However, simply implementing NIST controls without documented risk assessment, tailoring justification, and effectiveness validation fails to satisfy FISMA's requirement for comprehensive security programs.

FISMA and FedRAMP

The Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FedRAMP) applies FISMA requirements specifically to cloud service providers offering services to federal agencies. FedRAMP standardizes the security assessment and authorization process for cloud services, creating a "do once, use many times" framework where cloud providers achieve authorization that multiple agencies can leverage.

While FISMA broadly covers all federal information systems, FedRAMP provides a specialized implementation pathway for cloud services. Organizations offering cloud-based solutions to federal agencies typically pursue FedRAMP authorization rather than agency-specific FISMA authorizations—though both ultimately fulfill the same legislative security mandate.

Challenges and Common Misconceptions

Organizations frequently confuse FISMA certification with actual security. The authorization process focuses on documented evidence that controls exist and function—but documentation quality doesn't guarantee operational effectiveness. Too many organizations implement "paper compliance" programs that satisfy auditors while leaving systems fundamentally vulnerable to exploitation.

The difference between compliance checklists and meaningful cybersecurity posture becomes apparent when incidents occur. Organizations that view FISMA as documentation exercises rather than risk management disciplines discover their System Security Plans don't reflect operational reality, continuous monitoring produces data nobody analyzes, and incident response procedures exist only in policy documents.

Resource requirements for genuine FISMA compliance substantially exceed what many organizations anticipate. Establishing comprehensive system inventories, conducting thorough risk assessments, implementing and testing security controls, maintaining continuous monitoring capabilities, and producing required documentation typically demands 550-600 hours annually for self-managed approaches. Organizations underestimating this investment compromise either compliance quality or operational effectiveness—often both.

Federal agencies and their contractors frequently struggle with continuous monitoring requirements, treating authorization as terminal events rather than ongoing processes. All FISMA-accredited systems must monitor their selected security controls, with documentation updated to reflect changes and modifications to the system. Organizations lacking processes to detect control changes, assess security impact, and update authorization documentation face compliance drift where authorized configurations diverge from operational reality.

Conclusion

The Federal Information Security Management Act establishes comprehensive requirements for protecting federal information systems through risk-based security programs, documented control implementation, continuous monitoring, and sustained authorization processes. FISMA applies not only to federal agencies but extends to contractors, vendors, and any organization handling federal data—making it essential knowledge for enterprise technology companies pursuing federal contracts.

For vendors selling security solutions, cloud platforms, or enterprise software to federal buyers, understanding FISMA requirements represents competitive necessity. Federal procurement increasingly evaluates cybersecurity capabilities during source selection, making documented FISMA compliance a differentiator that accelerates contract award and demonstrates operational security maturity.

FISMA continues evolving with the threat landscape. The 2014 modernization strengthened continuous monitoring requirements and incident reporting obligations in response to increasing cyber threats against federal systems. Future amendments will likely emphasize automation, threat intelligence integration, and supply chain risk management as federal cybersecurity priorities shift to address emerging attack vectors.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is FISMA?

The Federal Information Security Management Act is United States federal law requiring federal agencies and organizations handling federal data to implement comprehensive information security programs. Originally enacted in 2002 as part of the E-Government Act and modernized in 2014, FISMA establishes requirements for risk management, security controls, continuous monitoring, and incident reporting to protect government information systems.

2. Who must comply with FISMA?

All federal executive branch agencies must comply with FISMA. Additionally, contractors, cloud service providers, managed service providers, software vendors, and any organization that stores, processes, or transmits federal information operates within FISMA's scope. State and local agencies receiving federal funding often face FISMA-aligned requirements as grant conditions.

3. How does FISMA classify systems?

FISMA uses FIPS 199 standards to categorize information systems into three impact levels—Low, Moderate, and High—based on potential harm from compromised confidentiality, integrity, or availability. This categorization determines which security controls from NIST SP 800-53 organizations must implement, with higher-impact systems requiring more rigorous controls.

4. Is FISMA the same as NIST?

FISMA is federal legislation mandating information security programs; NIST provides technical standards and guidelines for implementing those programs. FISMA establishes what must be achieved—risk-based security with documented controls—while NIST publications like SP 800-53 specify how to achieve compliance through detailed control catalogs and implementation guidance.

5. What happens during a FISMA audit?

FISMA requires annual security reviews where agency chief information officers assess information security program effectiveness and inspectors general conduct independent evaluations. These assessments examine system inventories, risk categorizations, security control implementation, continuous monitoring activities, incident response capabilities, and System Security Plan accuracy. Results are reported to OMB for oversight and consolidated reporting to Congress on federal cybersecurity posture.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)