Most enterprise buyers now request assurance artifacts before procurement. Without operational security and continuous evidence, deals stall—even when teams think they’re ready on paper. At the core of any mature security program is access control. The principle known as SOC 2 Least Privilege says that users, applications, and services should get only the permissions they need and only for as long as they need them.

In this guide we explore SOC 2 Least Privilege from the perspective of practitioners who have helped hundreds of companies pass audits and close deals. We look at why enterprise clients care, how it maps to the Trust Services Criteria, and what busy teams can do to make it real. We’ll share practical steps, examples, and templates to help you embed least privilege in your stack.

Why Least Privilege Matters in SOC 2 Compliance?

The principle of SOC 2 Least Privilege limits every user and process to the bare permissions needed for their job. NIST emphasises that each entity should have only “the minimum system resources, authority and privileges required”. In practice this means a support agent or developer does not share a root account and non‑human identities follow the same pattern. Separate roles or accounts are created for elevated tasks and removed when the task is done.

SOC 2’s Trust Services Criteria include security, availability, processing integrity, confidentiality and privacy. Only the security criterion is mandatory. Controls under security ask you to manage logical access, provision users properly and monitor privileged accounts. Restricting privileged accounts to security functions—such as audit settings and key management—helps satisfy this requirement. Fewer standing privileges reduce insider risk and make evidence collection easier.

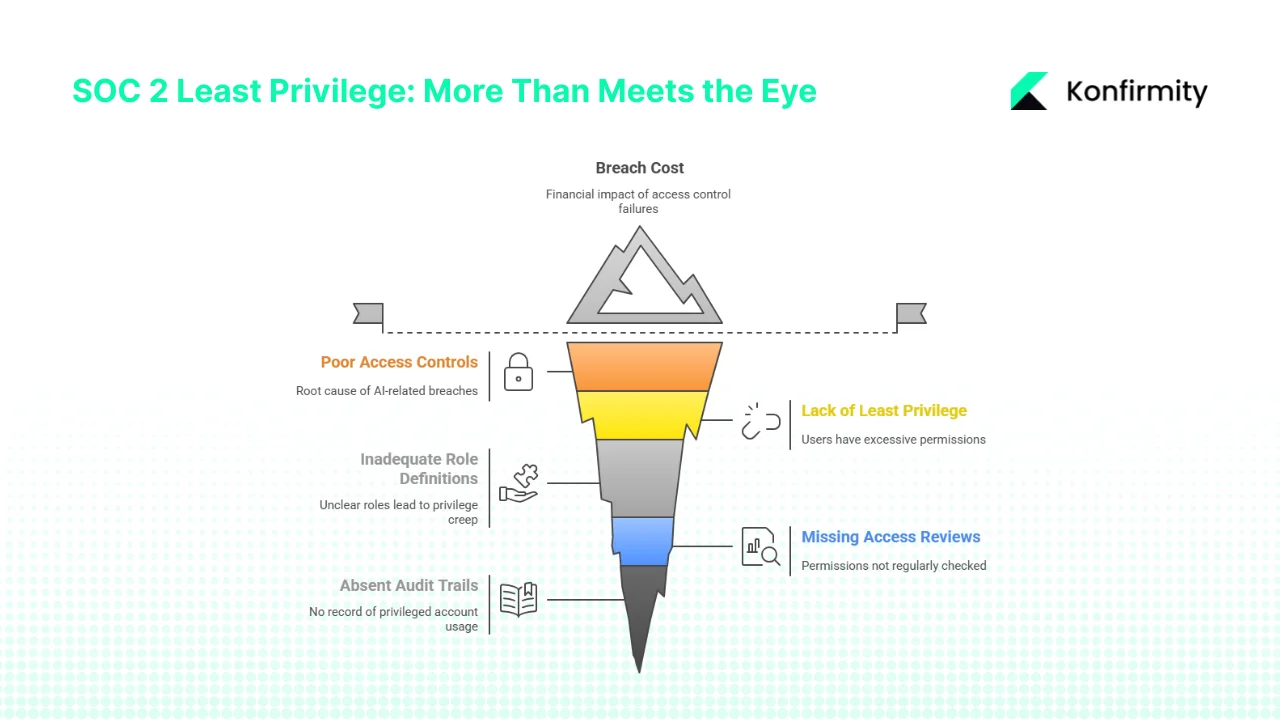

Enterprise clients care because they see the consequences when access controls fail. IBM’s 2025 breach report puts the global average breach cost at USD 4.44 million, rising to USD 10.22 million in the United States. It also notes that 97 percent of AI‑related breaches involved poor access controls. Buyers therefore look for proof that vendors implement least privilege: role definitions, access reviews, and audit trails. A well‑designed access model is not just a compliance box; it shortens procurement cycles and builds trust.

Core Concepts You Need to Know

1) Access control and role‑based access

Access control verifies identity and decides what a user can do. Role‑based access control (RBAC) groups permissions by job function so that engineers, support agents, or service accounts get only what their duties require. A clear role matrix helps you avoid “everyone has admin” problems and simplifies onboarding and offboarding. SOC 2 auditors routinely ask to see this matrix and proof that it is kept current.

2) Privileged user management

Administrators, root accounts, and certain service accounts can change configurations or view sensitive data. Verizon’s 2025 data breach report logged 825 incidents involving privilege misuse and 90 percent of attackers were insiders. Limit these accounts, require multi‑factor authentication, rotate credentials often, and maintain separate unprivileged accounts for routine work. Keep audit logs to trace activity.

3) Security policies and internal controls

A policy spells out who can approve access, how permissions are granted or revoked, and when reviews occur. Internal controls—such as monitoring and periodic reviews—make sure that the policy is followed. Auditors will ask for samples of access requests and revocations to verify that you act on your policy. If you also need to meet HIPAA or ISO 27001, align policies to those frameworks and ensure least privilege applies to PHI.

4) Data protection, risk mitigation, and audit readiness

Excess permissions invite trouble. Attackers often abuse unused or over‑broad accounts. NIST warns that privileged accounts should be limited to functions like audit settings and key management. Google’s threat horizons report found that weak or missing credentials were behind nearly 47 percent of cloud attacks. By designing least‑privilege roles and reviewing them regularly, you reduce risk and have the evidence auditors need.

5) How least privilege maps into SOC 2 criteria

SOC 2’s security criterion requires controls around provisioning, authentication, and authorization. Confidentiality and processing integrity also rely on limiting who can view or change data. A role matrix with minimal permissions satisfies these controls. For instance, CC6.1 asks management to restrict logical access to authorized users and applications. If you also select confidentiality, you must show that only those who handle confidential data can see it. Least privilege forms the foundation of these criteria.

This model also satisfies other frameworks. ISO 27001’s Annex A.9 requires access policies, HIPAA mandates role‑based controls for ePHI, and GDPR calls for data minimisation. Building one least‑privilege model reduces duplication across frameworks and ensures both security and privacy are addressed.

Step‑By‑Step Implementation Guide for Busy Teams

Implementing SOC 2 Least Privilege becomes manageable when broken into eight steps:

- Scope and inventory. List all systems and identities (human and service accounts) in scope. Record current permissions so you can spot over‑provisioned accounts.

Building this baseline allows you to identify hidden service accounts and legacy privileges that could become risk vectors. - Define roles. For each system, map job functions to minimal permissions. Build a role matrix for both humans and service accounts and distinguish between standard and privileged roles.

- Write policy. Draft a least‑privilege policy that sets out how access is requested, approved, reviewed, and revoked. Align review frequency with risk—quarterly for standard users, monthly for privileged users. Policies clarify expectations and set accountability, which makes enforcement less arbitrary and encourages compliance across departments.

- Implement tooling. Use IAM or PAM tools to enforce RBAC, require MFA on privileged accounts, and provide just‑in‑time elevation. Store service account secrets in a vault and rotate them regularly. Selecting the right tools up front saves rework and ensures your controls can scale as your team grows.

- Review and monitor. Conduct periodic access reviews comparing actual permissions to the role matrix. Remove unused accounts and adjust roles. Monitor logs to detect unusual activity.

- Handle exceptions. Define a break‑glass process for emergency access, including who can approve it and how logs are recorded. Revoke temporary access promptly and review the event.

A documented exception process ensures emergencies don’t become permanent backdoors and shows auditors that you take deviations seriously. - Collect evidence. Gather role definitions, access requests, approvals, revocations, and review reports. Map them to SOC 2 criteria so auditors can see your controls operating over time.

- Sustain and adapt. Integrate least privilege into hiring, offboarding, and new system rollout. Update roles and policies when the business or tech stack changes. Treat it as part of your continuous compliance program.

Practical Examples and Template Snippets

Example role–permission matrix

Use this table to define who can do what. It also sets how often you should revisit each role. This matrix is central to your SOC 2 Least Privilege implementation.

Policy template excerpt: Least Privilege Access Policy

- Scope: This policy applies to all employees, contractors, service accounts, and third‑party users of Company systems.

- Principle: Users and non‑human identities shall be granted only the permissions necessary to perform their assigned tasks. Elevated privileges must be time‑bound and approved by an authorized approver.

- Reviews: Access shall be reviewed at least quarterly for standard accounts and monthly for privileged accounts.

- Revocation: Access shall be revoked promptly upon termination of employment, change of role, or completion of a project. Privileged credentials must be rotated on a defined schedule.

Privileged user management checklist (condensed)

- Identify and name each privileged account.

- Require MFA and store credentials in a vault with regular rotation.

- Review privileged accounts monthly and remove unused ones.

Access review report template

Record who is being reviewed, their role, the system, and whether to reduce or remove access. Include a date and reviewer signature separately.

Exception or break‑glass workflow template

- The engineer raises an emergency access request.

- An authorized manager approves the request and sets an expiry.

- Temporary access is granted and logged.

- After the incident, the access is revoked and the event is reviewed.

Mapping to SOC 2 internal controls

This mini‑table connects least‑privilege activities with the relevant SOC 2 controls and indicates what evidence auditors will expect.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

- Privilege accumulation and ignored accounts. Users and service accounts can accumulate permissions over time. Without regular reviews, roles balloon. Schedule quarterly reviews and assign owners to service accounts so stale privileges are caught and removed.

- Granting broad permissions. Avoid giving admin rights “just in case.” Define minimal permissions and use temporary elevation when needed.

- Lack of documentation and evidence. Break‑glass access and emergency changes should be approved, logged, and reviewed. A good policy is only the start; auditors will want to see that controls work over time.

Using Least Privilege as a Competitive Advantage

Enterprise buyers judge vendors by the maturity of their controls. Evidence of SOC 2 Least Privilege—rare standing privileges, regular reviews, clear logs—signals a strong security posture and can accelerate deals. Risk teams often run vendor security questionnaires that probe for role definitions, privileged account management, and access review cadence. When you can answer quickly and back your answers with artifacts, procurement moves faster and trust builds.

In our experience supporting more than 6,000 audits, self‑managed teams often spend 500–600 hours preparing for SOC 2, whereas a managed service reaches readiness in about five months with roughly 75 percent less internal effort. Fewer findings and faster procurement are common results. Organizations subject to HIPAA can reuse least‑privilege evidence for both HIPAA and SOC 2 because the principle aligns with role‑based access requirements for ePHI.

CTA: Book a demo

Conclusion

Least privilege reduces risk and helps prove trustworthiness to clients and auditors. Define roles, manage privileged accounts, document policies, and review access often. Breaches remain costly—US companies face averages over USD 10 million per incident, and weak access controls are a common cause. A managed approach to SOC 2 Least Privilege reduces that risk and frees teams from reinventing processes. Start by inventorying access and building a role matrix. Draft a policy, enforce it with tools, run reviews, and collect evidence. Controls must work every day, not just on paper. Build them once and keep them running so compliance follows naturally. Your program should stand up to buyers, auditors, and attackers and protect your brand and reputation today.

FAQ

1) What is the least privilege in SOC 2?

In the SOC 2 context, least privilege means that each user or process gets only the permissions needed to perform its job. The principle extends to non‑human identities like service accounts. NIST defines least privilege as giving each entity “the minimum system resources, authority, and privileges required to perform the task”. SOC 2’s security criterion requires organizations to restrict logical access to authorized users and processes and to enforce this through controls such as RBAC. By limiting access, you reduce the attack surface and make it easier to prove to auditors that you know who can do what.

2) What are the mandatory criteria for SOC 2?

SOC 2 consists of five Trust Services Criteria: security, availability, processing integrity, confidentiality, and privacy. The security criterion is mandatory for all SOC 2 audits. The other criteria are optional and can be selected based on your business. For example, companies that host applications may include availability, while those that handle personal data may include confidentiality and privacy. Your auditor will confirm which criteria apply to your scope. Even when optional criteria are not selected, the principle of least privilege still helps because it underpins security across all areas.

3) What is a SOC 2 exception?

An exception in a SOC 2 report is a finding where a control did not operate as designed. It might be a user granted access without proper approval or a privileged account that wasn’t reviewed. Exceptions are not automatic failures; they show areas for improvement and may lead to observations or qualifications in the report. To handle exceptions, document them in an exception register, conduct a root‑cause analysis, and implement corrective actions. For example, if an engineer used a shared admin account during an incident, document why, record the approval, and update your process to avoid recurrence.

4) What is a SOC 2 Type 2 policy?

SOC 2 audits come in two flavors: Type 1 and Type 2. A Type 1 report evaluates the design of controls at a point in time, while a Type 2 report evaluates both design and operational effectiveness over a period—commonly six to twelve months. Auditors sample transactions across this window to see whether controls work under real conditions. A “Type 2 policy” is therefore a policy that is not only drafted but consistently enforced. In least‑privilege terms, you must show evidence of access requests, approvals, reviews, and revocations spanning the observation period. If your scope covers dozens of controls—SOC 2 Type II reports often cover 60 to 80 control points—each one needs supporting evidence. Auditors will ask for tickets, logs, and reports to verify that controls operate continuously, not just on paper. Organizations aiming for Type 2 reports should embed least privilege into day‑to‑day processes, automate evidence collection where possible, and run internal checks during the period to avoid surprises at the audit’s end.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)